The term voice recording software, especially in the context of recording voice overs, is actually sort of a misleading term. That’s because pretty much any software that is designed for recording on a computer is going to be just as capable of recording the human voice as any other audio. So the real question, becomes something more like “what else other than voice recording will I need to do with a particular audio recording program?”

The term voice recording software, especially in the context of recording voice overs, is actually sort of a misleading term. That’s because pretty much any software that is designed for recording on a computer is going to be just as capable of recording the human voice as any other audio. So the real question, becomes something more like “what else other than voice recording will I need to do with a particular audio recording program?”

Let’s take an example. Many folks use a free recording program called Audacity, which is pretty darned amazing for a piece of free-ware. If all you ever really want to do is record your voice to do introductions for your own programs, videos or podcasts, Audacity is likely to be the only audio software you’ll ever need. It has the ability to record at high resolution, do basic edits and produce professional sounding audio.

If, on the other hand, you also want to record music, especially involving multiple tracks or in-depth and intuitive editing, Audacity probably isn’t your best choice. Once you get beyond the basic “push-record/stop/play” functions, Audacity loses out on simplicity and capability. It becomes worth your time and money at that point to use two programs, one designed for recording and mixing, and the other designed for editing and finishing/producing.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but think of it this way. It is ultimately better for your workflow, not only physically but mentally as well, if you can compartmentalize discrete tasks, especially when the software being

used is specifically designed for that purpose. The more focused the reason for a program, the faster and more intuitive it tends to be for users. In my case, I use a program called Reaper (by Cockos), for recording and mixing, then I use another program called Adobe Audition for editing and final production. This workflow is so natural to me that even if I need to record a quick voice over job, I open Reaper to do the recording, then I double-click on the audio item on the track to automatically open my editing program, Audition. I can then quickly reduce ambient noise, fix p-pops, even out and optimize volume, and save as any format I want.

Now obviously these are not the only two programs out there you can use for this kind of work-flow. You could use Reaper + Audacity, for example. There are also some really affordable, intuitive and powerful new-comers, such as Mixcraft 8 for recording and mixing. And if you need more capability or better workflow than Audacity can provide, a really good (and much more affordable than Audition) alternative is WavePad Sound Editor.

So basically it comes down to this. Any recording program is going to be at least as good at recording voice as it is at recording anything else, so don’t worry about looking for voice recording software so much as something more generic, like audio recording software. At that point, you just have to know what capabilities you’ll need. Extremely basic voice over jobs, like for your YouTube videos or podcasts, can be handled by something like Audacity. But if you want to ad any capability beyond that, the best choice is to divide and conquer with two programs working together, one for recording and mixing, and the other for editing and final production.

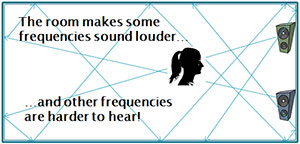

Well, if my room tends to amplify bass frequencies, my ears would tell me that there was too much bass in a song when there really wasn’t! So I might respond by turning the bass down on the

Well, if my room tends to amplify bass frequencies, my ears would tell me that there was too much bass in a song when there really wasn’t! So I might respond by turning the bass down on the