What dos it mean to master a song? Let’s hear from an expert.

Known for his 20 years of experience in the music industry, with artists like Lady Gaga and Rhianna just to name a few, music producer Marc JB breaks down the art of mastering. He also breaks down the techniques you need need to create your own epic tracks.

Although it often made to seem a mysterious, tedious and expensive thing, mastering is quite simple once you understand its nooks and crannies.

Marc JB describes good mastering as balanced, clear, present and loud. If it sounds good on a variety of systems then that’s a success.

Mastering is basically just stuff you do in the final stage after a recording is mixed down.

Read the tips from Marc here: http://www.musictech.net/2017/07/get-hands-on-with-mastering-the-basics-part-1/

You might also be interested in our posts: Mastering a Song – What Does It Mean? and Home Recording For Non-Engineers – It’s Not Hard Or Expensive

mastering

What is Equalization, Usually Called EQ?

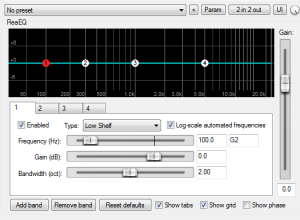

EQ…That Thing You Never Knew Quite How To Use

EQ…That Thing You Never Knew Quite How To Use

Have you ever seen one of these things? They used to be common in “entertainment systems.” Right along with your CD Player, Cassette Player, Record Player, amplifier, and “tuner” (meaning…”radio”), would be this other big boxy thing with nothing but a row like 30 vertical (meaning “uppy-downy”) slider controls across the face of it.

These sliders had little square button-like thingies that you could slide up or down. They usually started out in the middle (at the “zero” mark). About the only thing they seemed good for is making funny patterns, like smiley faces, or mountain ranges, by moving the sliders up or down in the right way. Besides maybe making you feel better by having your stereo “smile” at you, I really don’t think anybody ever knew what to do with one of these things.

But it sounds scary

With a scary name like “graphic equalizer,” it sounded so important. It also sounded like a good name for a “rated-R” action movie, but that’s another story. Anyway, you had to make everyone think you knew why you had one, so you pretended to know what it did. But in reality, you felt safer just leaving it alone to sit there with its straight row of slider buttons right down the center, the way it was the day you brought it home because it came with all the other stuff.

You are probably familiar with some kinds of EQ without realizing it. You know those controls on your music player labeled “bass” and “treble”?” That’s a crude EQ! If your graphic EQ box had only 2 little sliders on it, it would be the same thing. One control makes the sound “bassier” (the low sounds) and the other makes the sound “treblier” (the high sounds).

I always laugh when I see someone turn both controls all the way up or down. They have accomplished absolutely nothing that the volume knob wouldn’t do. If both (all) the sliders are up, you just turned the radio up. Congratulations. An EQ is only useful if you can make shapes OTHER than straight lines with the sliders.

So now you’re wondering what the heck an EQ IS good for aren’t you? Well for one thing, it turns out that our ears lie to us! Can you believe it? I know! It’s crazy, right? Every human has lying ears. I was floored when I first heard.

It turns out that there are all kinds of sounds out there in the world that we can’t hear! As a matter of fact, MOST sounds are inaudible to humans. The only sounds humans CAN hear are those in the range between 20 hertz (abbreviated as “Hz”) and 20,000 Hz. A “hertz” is a measure of how often (or “frequently”) something shakes back and forth (or “vibrates”) in one second. See the video below.

Sound is just energy that makes air particles shake back-and-forth. When these air particles vibrate with a frequency of between 20 times and 20-thousand times per second, it makes a sound that is in the “range of human hearing.” Though if you’re 21 or older, good luck hearing things above 16,000 Hz;) (where the so called “teen buzz” or “mosquito frequency” lives. Confused? Ask a teenager.

Some Particular Sounds Are On the Same Predictable Place On The Frequency Spectrum

In the frequency spectrum between 20-20 thousand Hz (usually abbreviated as “KHz”), some amazing things happen.

One interesting example is that a baby’s cry is at perhaps the most annoying frequency there is, around 3KHz. I say “annoying” because humans are MOST sensitive to sounds at that frequency.

This may be a survival thing for us. But since we don’t usually have a “crying baby” solo in our audio recordings, why is this helpful?

What that means is that everything we can hear vibrates around certain predictable frequencies. And knowing that gives us some pretty cool superpowers.

For example, I know just where to find the signal of a bass guitar on the spectrum. It’ll be down around the low frequencies of 80-100 Hz. So will the kick drum. The electric guitar will usually be in the mid-range between 500Hz and 1KHz in the upper mid-range along with keyboards, violas and acoustic guitars and human voices. Clarinets, violins, and harmonica’s tend to hang out mainly in the upper-mid range around 2-5 KHz, and things like cymbals, castanets, and tambourines like to be in the “highs’ up around the 6 KHz.

Just ignore the fact that, in a range that tops out at 20KHz, we call things at 7 or 8 KHz “highs.” It’s because the spectrum is exponential, and not linear. If that makes your brain hurt just ignore it. It’s sometimes better that way.

Now that we know where specific things live in the range of hearing, we can adjust volumes at JUST those frequencies without affecting the rest of the audio.

Knowledge of this “range of human hearing,” and how to use (or NOT use) an EQ will come in handy more often than almost any knowledge. Once we know where to quickly find where a sound is on the EQ spectrum, we can surgically enhance, remove, or otherwise shape sounds at JUST their own frequencies, without affecting other sounds at other frequencies.

But how in the world can we adjust volume in just one narrow frequency, say 100 Hz, without also changing the volume at all the frequencies? Hmm, wasn’t there some discussion about a thing called an “EQ” that had a whole bunch of sliders on it? Could it be that those sliders were located as specific frequencies, and could turn the volume up or down just at those frequencies without affecting the rest of the sound? Why, yes. It could be. Now you know.

This video is an excerpt from The Newbies Guide To Audio Recording Awesomeness 1: The Basics With Audacity, and should really help you understand all this stuff better. It breaks things down to the simplest basics – and might even make you laugh a little:-).

Mixing With EQ Instead of Volume Controls

Once you know where the frequencies of certain instruments are likely to live, you can use an EQ to prevent these sounds from stepping all over each other in a mix and sounding like a jumbled mess, with bass guitar covering the sound of a kick-drum, or the keyboard drowning out the guitar. “But you wouldn’t need to use an EQ to do this if you use a ‘multi-track’ recorder, right?” That’s what recording engineers and producers usually use to record bands, and other musical acts, so each instrument and voice is recorded onto their very own “track.” Since every different sound has their own volume control, it seems obvious what to do if something is too loud or quiet, right? ‘Don’t you just simply use a mixer to turn the “too loud” track down, and vice versa. I mean, isn’t that what “mixing” means?’ That’s what I used to think too. The answer is… “only sometimes.” For example, even after spending hours mixing a song one day, I simply could NOT hear the harmonies over the other instruments unless I turned them up so loud that they sounded way out-of-balance with the lead vocal. It was like a bad arcade game. There was simply no volume I could find for the harmonies that was “right.” It was either lost in the crowd of other sounds, or it was too loud in the mix.

Then I learned about the best use of EQ, which is to “shape” different sounds so that they don’t live in the same, over-crowded small car. Let’s say you have one really, really fat guy and one skinny guy trying to fit into the back seat of a Volkswagen Bug. There is only enough room for 2 average-sized people, and the fat guy takes up the space of both of those average people already. Somebody is going to be sitting on TOP of someone else! If the fat guy is sitting on the skinny guy, Jack Spratt disappears almost completely. If Jack sits on top of Fat Albert, he will be shoved into the ceiling, have no way to put a seatbelt on, it’s just all kinds of ugly no matter which way you shove ’em in.

But if I had a “People Equalizer” (PE?), I could use it to “shape” Albert’s girth, scooping away fat until he fit nicely into one side of the seat, making plenty of room for Jack. Then if I wanted to, I could shape Jack a bit in the other direction, maybe some padding to his bony arse so he could more comfortably sit in his seat. Jack just played the role of the “harmonies” from my earlier mixing disaster. Albert was the acoustic guitar. Just trying to “mix” the track volumes in my song was like moving Jack and Albert around in the back seat. There was no right answer. But knowing that skinny guys who sing harmony usually take up space primarily between 500 and 3,000 Hz, while fat guitar players can take up a huge space between 100 and 5,000 hertz, I can afford to slim the guitar down by scooping some of it out between, say, 1-2KHz, and then push the harmonies through that hole I just made by boosting its EQ in the same spot (1-2 KHz). Nobody would be able to tell that there was any piece of the guitar sound missing because there was so much of it left over that it could still be heard just fine. But now, so can the harmonies…because we gave them their own space! And we did all this without even touching the volume controls on the mixer. So it turns out the EQ does have it’s uses!

Cheers!

Ken

Tips For Mastering Your Own Music

If I could have my way all the time (shya!), I would never master my own music. Why? Because there are people out there who do NOTHING but audio mastering all day every day. It’s a highly specialized skill, and the people who do it professionally have super developed hearing and, usually, high-end gear designed for the purpose.

If I could have my way all the time (shya!), I would never master my own music. Why? Because there are people out there who do NOTHING but audio mastering all day every day. It’s a highly specialized skill, and the people who do it professionally have super developed hearing and, usually, high-end gear designed for the purpose.

However, I understand that I will NOT have my way all the time. And that means I won’t always have as much money as I would like (well, who does?:)). So it is sometimes necessary to do your own mastering. For times like those, it is best to have at least SOME knowledge of what you’re doing and why you’re doing it.

For an overview of what mastering is, you can check out my article Mastering a Song – What Does It Mean?

Here is a handy article with twenty additional tips for mastering your own audio:

http://www.musictech.net/2015/02/twenty-mastering-tips/

Transcript Of My Interview With Thaddeus Moore

I interviewed Thaddeus Moore, Chief Mastering Engineer at Liquid Mastering (liquidmastering.com) last Thursday evening. I wrote about it the next day, and put up a few of the highlights there – Interview With Mastering Engineer – Thaddeus Moore. In that post, I promised a full transcript of the interview. So here is that transcript! Enjoy!

I interviewed Thaddeus Moore, Chief Mastering Engineer at Liquid Mastering (liquidmastering.com) last Thursday evening. I wrote about it the next day, and put up a few of the highlights there – Interview With Mastering Engineer – Thaddeus Moore. In that post, I promised a full transcript of the interview. So here is that transcript! Enjoy!

Transcript From The Interview – A Google Hangout On Air

Home Brew Audio (Ken Theriot): Well, welcome everyone to our hangout with Thaddeus Moore. Thaddeus, is the Chief Mastering Engineer for Liquid Mastering, has over 17 years of experience in many fields of audio engineering, including, of course, mastering. But we hope to pick his brain on basically, any topic related to home recording, audio recording, especially music recording, tracking, mixing, and mastering. So, welcome, Thaddeus.

Thaddeus Moore: Thanks for having me.

HBA: We are honored to be able to have this interview with you. We have people who are asking all the time, just general questions, “What was the number one thing that you would recommend I do? How do I get into recording?” And I have some questions that people have sent me already queued up along those lines, but if we could start out with just kind of overarching… We talked earlier about some advice that you feel doesn’t get out there often enough. Can you fill us in on what some of that is?

TM: Well, when it’s coming to your own music, the best thing that you can do is focus on content and space, as far as writing your compositions. There’s no better gear for a song than a good song, a well arranged song. The way the parts fit together makes the song work. And we all have a tendency, once you get into this engineering field, to get super gear-focused, and there’s some great gear and I use a lot of really expensive fun toys to do my thing, but really, when it comes right down to it, if the song is well built, it’s easy… So, it’s all about the songwriting. So… But as far as how to maintain your files if you’re working at home alone, it just… It really depends on what system, what architecture, if you’re in Mac or PC, there’s slightly different ways that you have to maintain your files.

TM: So, I’m not sure what would be the best for your viewers, what the people that are into what you’re doing or asking, but file management is a huge, huge issue for people. One of the things that I deal with the most now from people who are working either by themselves or with a friend who’s engineering their work in a home studio situation, which is pretty common, there’s so many different formats of files and there’s so many different ways that you can trade files over the internet. And keeping track of that is a really, really important task. It’s boring for a lot of people, they don’t wanna think about it. But if you want to be able to do a remix 10 years from now on a song of yours, paying attention to that now is the most important thing you can do.

TM: Making sure that all of your source files are contiguous, meaning in whatever DAW you’re working in, I’m assuming most people are working digitally, if you’re working on analog, great, but you already know what to do. But with digital files, if you’re punching in different parts of the song, you’ve got verse one, chorus one, you’ve got these different sections of audio possibly in the same track, let’s say it’s a vocal, in order to maintain that integrity of where those samples are placed throughout your song, you need to do what’s normally referred to as a “consolidation” on that file at the end.

TM: Usually, it’s at the final, and that’s where I deal with most of this stuff is at the very end of somebody’s production and how they’re getting their files maximized for what they’re gonna send it off to do. It doesn’t really have to do with mastering because I don’t really see the individual tracks like that. I just get it mixed down, WAV file usually. But it is a really important thing for people to do, is to make sure that you have a consolidated… And each program calls it something different. In Performer, it’s called merge bytes. In Pro Tools, it’s called consolidate regions. In Logic, it’s called bounce in place. So, you have to do research about your particular DAW and what it calls that function. But, what it…

HBA: They call it glue in REAPER, “Glue Items.”

TM: Right. Glue in REAPER. Right. And I’m constant… I’m gonna actually put up a page about this on my site soon. But… Because I really feel like even though I don’t have much to do with it, I think it’s a really important thing for people to do, because then, from now on, you’re not locked to whatever DAW you originally recorded it in. For example, I have files sometimes come to me from 10, almost 15 years ago, people working on early versions of Pro Tools, and they can’t even open them because their version of Pro Tools doesn’t exist anymore. So, they have all these tiny little punch point pieces that they have to try to piece a song together, and if what you have is a consolidated region or a glue, or whatever it’s called, then you just need to make sure they all have the same zero point in time. And that way you can drag them in to any DAW in the future. Going forward, from here on, it’ll always be a standard.

HBA: It doesn’t matter if it’s Mac, PC, or other, it will be able to line up those tracks and all of your song will be built the way that it was originally intended. So, that’s super important and I highly recommend balancing everything at 24-bit or better, at 44:1 or better, and also making sure to use one of the more common file types. The two that are really hanging on now are WAV, everybody knows that. AIF is another pretty common format. Sound Designer II or SDII, they’ve kinda died away, that was the original before Pro Tools came along but they’re all pretty interchangeable at this point. But you don’t… You definitely don’t wanna convert all your source material into some lossless format, like MP3 or AAC because… And we should talk about that at some point. But that’s all I wanted to say on that. We can go on and get to some of the other questions that you people are asking here, so…

HBA: That’s great advice, absolutely, ’cause, yeah, I work… In fact, one of the courses we have at Home Brew Audio is the DAW that I use and that I teach is REAPER. And they’ve got two different procedures you can do with a song. You can save stems for a complete song, which will do what you say and it will glue everything in place and each track then will be its own contiguous thing, and it will come out as a ZIP file of track one, track two, track three, track four, or whatever you named each track. But then there’s an “export as project” as well, which will be… It will be readable across all formats. So, that’s another way to send files. But as a mastering person, you usually just receive the WAV, right?

TM: I receive the final, usually a two-track, if you’re just working in stereo mixdown, so a left and right WAV file. And I really like to see 24-bit or better. Even if you’re working at 16-bit in your DAW, it’s still a good idea to bounce your final mix out at the 24-bit. But you gotta make sure you do that native, and that you’re not bouncing 16-bit and then upsampling to 24 because that gets you nothing. Once you go down in bit reduction, you’re pretty much stuck at that level. I use a lot of analog processing in my mastering, so I’ll go out and I’ll hit some analog gear and then come back in. Sometimes I need to do that with some of the lower quality stuff just to get things to sound a little bit more alive. But it really depends, every song is different. But if you stay at the highest quality, you have a better chance of ending up even better. It’s like… Another mastering engineer uses the term like, “I can move a mix up a letter grade. So if you have a C+ mix, I can give you a B-.”

HBA: It’s like, “I can work up if you give me something to work from. If you’ve got an F mix, it’s probably gonna turn out to be a D master, but I’ll do my best.” And I usually try to give people feedback on their mix before I do my thing. If I think something’s really not gelled together and they have the ability to go back to the mix stage and fix it, I always tell people that upfront rather than trying to fight through it and ending up taking up of their time for nothing.

HBA: Well, I would like, if you don’t mind, to start out with a few questions on the tracking and mixing stage for some of the folks and then, we’ll get into the questions on mastering. First of all, just a quick opinion, do you think people can produce professional-sounding recordings in home studios in 2014?

TM: Absolutely. I’m not sure what “professional” means anymore. It’s up to the listener whether they like it. I’ve heard some really lo-fi, beautiful sounding music that it fit the mode of what they were trying to say as an artist. So from my point of view, there’s always been professional level recording at home. Ever since recording came out, one of the first multi-track recordings was done by Les Paul and his wife on their…

HBA: Oh, Mary Ford, yes.

TM: On their home recordings, this in their basement. So there’s always been the ability to make professional recordings at home. Right now is a particularly good time to get into the digital recording side of things because it’s finally starting to sound really good. I’ve heard things people have done on their iPad that sounded awesome, literally awesome, and that’s crazy. It’s amazing, beautiful. It’s a great time to be in the music world because of that. Music business is having some hard times with it, but music is very healthy.

HBA: Yeah. Well, I always try to tell people that it’s, like you said earlier, less about the gear and more about sort of what you do with it.

TM: Yeah, it’s all about the song and it’s about the composition and it’s about the voice, not necessarily the human vocal, but it’s about what is trying to be said in the music. It’s why music matters so much to so many people, because of how much it can speak directly to your subconscious being. So it’s… None of the gear that I use to do my thing is gonna change that. What I can change is how something’s gonna sound on multiple different speaker systems, on different kinds of headphones and try to help things congeal a little bit more, maybe have a little bit more punch, dynamic, range. Whatever the song is lacking, I can do a lot of really fun stuff in the mastering stage. But really if the song’s not a good song, it doesn’t matter. There’s only so much you can polish a turd…

TM: It’s still a turd. So make the best music you can and we’ll all thank you for it, all of us music-heads. We’re all in this together. We all love music for the very reasons we’re talking about.

HBA: Well, along those lines, I had a discussion with somebody at our release concert, who is a music manager for a radio station, who said, “There are a lot of people in our group. We have this sort of a niche that do recordings, but they don’t sound professional, and yours do and what is the difference?” And I don’t know how to answer her. I’m trying to come up with ways. What would be your take on that? What would be the top three things that amateurs do wrong when recording and mixing?

TM: I think there’s a lot of bass management issues. A lot of the things that I here of people who don’t have the experience in recording as much, don’t know how to control the low end of the mix and it ends up dominating a lot of the time and sounding really woofy and harsh. On the other end of the spectrum, people who don’t know how to place a mic well just end up getting all this other room ambience or something in their recording that’s making it sound muddy and not clear. There’s a lot to do with mic technique, choosing the right microphone and placing it in the right position, because microphones are like… A lot of people talk about microphones as being directional because every microphone has a polar pattern, and I don’t know if you’ve talked about that yet but…

HBA: Yeah.

TM: The microphone that you’re using right now, that microphone has a switchable polar pattern from Omni, Figure 8 or Cardioid which is mostly one-sided, and each one of those has their benefits for different kinds of uses. But not only are microphones directional, which, what direction they’re gonna pick up sound sources from, they’re also a dropper. They’re like taking a little sample dropper of that little tiny cubic portion of air that the capsule sits in. So, if you point a microphone at your sound source and then move that microphone closer or further away, you will hear a huge difference in frequency spread, because different frequencies develop differently over space. So, you’re gonna have a different sonic characteristic depending on how far away or close your microphone is to its sound source. And sometimes it’s great to get a nice, far away, warm luscious room sound; and sometimes it’s nice to be just right up in the grill, just getting the very essence of what that thing is. Sometimes it’s nice to use both.

TM: I don’t know how you guys tracked. I don’t know how the people they’re saying it didn’t sound professional tracked, but a lot of the time it has a lot to do with song composition. I mean, really, I… For example, I’ve been running a studio as well as mastering for almost 18 years. It’s amazing the difference in two bands. For example, I had the exact same drum kit, it was my studio kit. It was a really nice, well tuned, really nice, five-piece Yamaha custom kit. First day, set up all the mics, got it sounding really good. The drummer really knew what they were doing. The band sounded awesome.

TM: We left it set up and used the same exact set up, left all the mic pre-amps on, same settings, came in the next day with a different drummer, and it sounded terrible. And nothing we could do was fixing it, because there’s a lot to be said about technique. And I’m just talking about drums right there but in every instrument, proper tuning, proper placement of notes with other people who are playing in the band, I mean, that is huge, and it’s hard to even put a qualification on it, like, “Oh, that song sounds professional probably because you guys are just a tighter group. You’re a tighter band and your music comes across that way, more so than any recording technique.” You know what I mean? It’s hard to say until I hear it back and forth. If I had some examples, I could probably tell you what might have been able to be done better in certain circumstances, but there’s too many variables, there’s too many variables.

HBA: The two things that I was able to, I think, put my finger on which one of them tracks, exactly with what you’re talking about a lot of us are recording a one-man-band kind of things. I do a lot of… I’ve been in rock bands, but right now, I’m doing mostly acoustic stuff, so, I’m layering my own tracks and playing acoustic guitar, and then I’ll play the bass, and then I’ll add different kinds of drums and sample drums, and some hand drums or something later, and then add some other instruments, and then add a bunch of harmonies, because I love doing that, but I am…

TM: [laughter] Everything you just said, you didn’t talk about gear at all just now. It was all about the song and the way that you put it together. That’s my opinion is that what makes something sound more professional is the song writing.

HBA: And I had one example of one of the recordings I was listening to, that she had put in that other category, that some of the songs were extremely good as compositions, but the person had… What’s the way to put it? I’m probably a little too far into the details. I’m just psycho about it and my wife has to drag me, kicking and screaming away from the computer, going, “No, it doesn’t need to be three microseconds more correct in sync with the bass.” You know, that kind of thing. But if I hear anything out of sync with anything else, it makes me crazy, and I’ll go in and slice one beat and drag it left or right, a couple of literally microseconds, to get it to where it’s more correct, and what I heard in this other recording was that they didn’t… Not only did they not drag it one way or the other, they didn’t seem to pay attention at all. There was a drunk track in the background that didn’t track and didn’t sync with the guitars, and it was slipping and sliding forward and back, ahead of the beat, behind the beat and other instruments as well. That drove me nuts.

TM: I mean there are some bands that have made a thing out of that, that are able to attract a certain group of people because of how discordant or noisy, or erratic or whatever it is that they’re doing, but usually that’s the point. Its not a band that’s trying to be one way and failing and just saying, “Oh well, whatever.” It’s… That’s professionalism. It’s taking it seriously, making sure that you have good takes of the players. I’ve heard some great recordings done with one microphone like an SM57 hanging above the drums in a room with a band that was ridiculously tight at what they did that sound better than some full productions with multitrack and all these overdubs and everything because the source tracks weren’t built right. So, yeah.

HBA: Exactly, so… The other thing… I’m sorry, go ahead.

TM: You answered your own question.

HBA: Yeah.

TM: It’s all about professionalism.

HBA: Yeah, yeah. That’s pretty scary stuff. I should do this more often so that I can gain more knowledge. Let’s see. I would ask… You said that we were gonna talk a little bit about gear. Does it matter that much about gear, but they’re a lot of people who are asking about recording. “I wanna get into it, but I don’t know what to do and I don’t have a large budget.”

TM: Okay.

HBA: So what would your advice be for someone like that?

TM: It really depends on what their budget is and what they’re trying to achieve. If they’re an EDM artist, and they’re just trying to make really fun beats of whatever kind, it’s really easy nowadays to just get different pieces of software free stuff. Mac or PC, some even just right in the web that you can start building sequencing right there. You don’t have to spend much at all. But if you’re wanting to do live tracking of any kind, the most important thing is your microphone, hands down. It’s the point at which you’re capturing what’s the essence of what it is you’re trying to record. So if you’re gonna spend any money, spend it on a good microphone, but with digital recorders, you also have to have an interface and unfortunately, there’s a huge variance in quality difference in different kinds of converters. And what I mean by a converter, usually it’s for a home recorder, it’s just gonna be a standalone box that maybe has two mic pre-amps in it and analog to digital converters and then maybe a headphone out with some digitals to analog converters back the other way.

TM: Maybe it’s USB or FireWire or Thunderbolt now. Those are where I would spend the most money. Spend money on something like a good microphone and spend money on something like a good microphone pre-amp and converter setup and that’s… You’re off and running because software is basically free now. You can get just about any kind of software you want, try it out and I mean, you’ll love REAPER and what is it, $60.00 or something?

HBA: It’s $60.00. Yeah.

TM: Just pay them. They’re great at what they do. They’re really responsive, they have a great forum of people that use that software, it’s written by just a couple of guys who are just doing it because they love it. That’s the kind of thing I love. It’s great. Just get a good mic, get a good mic pre-amp setup and get REAPER. That’s… It doesn’t matter. The DAW does not matter. It’s more about what you feel comfortable with, what works well, isn’t glitchy and dropping files and crashing all the time. It’s more about what you can really use. It doesn’t matter what it is. I teach classes on audio engineering and that’s one of the things people ask me all the time, “What’s a better DAW?” And if all you’re trying to do is get ideas down and you have a Mac, GarageBand is free. It comes with it and it’s just right there, ready to go, and it’s not a great program by any means.

HBA: Yeah.

TM: But it’s definitely not the worst thing I’ve ever seen. You can write songs in it. You can do really fast edits. It’s missing a lot of basic features, in my opinion, like cross fades. I don’t know why they don’t have that in there, but… So anyway, as far as gear is concerned, really, the microphone is where to go. It’s where to look and the microphone that you’re using is one of my biggest recommendations because it is such a jack of all trades. It’s got a really great frequency response, it’s got really directional polar patterns. I love its figure-eight. I use it on figure-eight a lot when I’m tracking. I have a lot of mics. I’ve got a lot of different microphones, but if somebody was on a low budget, that’s one of the best mics you can buy for the money. Best bang for your buck, so.

HBA: And for those who wonder, this is the mic he’s talking about which is a Rode, R-O-D-E, NT2-A. This is multi-pattern. They also make an NT1-A. It doesn’t have the same capsule as the NT2-A and it’s a Cardioid only, but it’s less expensive.

TM: I prefer that NT2-A over the NT1-A, but each their own. If you like it better, by all means. I had the chance once to work with a $6,000 beautiful tube mic that everybody around me was talking about for weeks, I couldn’t get anything out of it that I enjoyed. It was just amazing. So it really doesn’t matter, as long as you are getting what you want out of it, it’s a good microphone.

HBA: [laughter] Awesome, yeah, people talk about like, “Well, Jeff Lynne uses an SM57 on his voice in the studio” or whatever, it’s…

TM: There you go!

HBA: Yeah, so it’s what sounds better, what sounds good. What is your opinion on how far USB mics have come?

TM: I really haven’t had much experience with the USB mics but there’s a lot of them out there, so I would imagine the two frontrunners in that competition are probably RØDE because they’ve been doing it for one of the longest, and Blue. I would imagine both of theirs, have great different settings. I don’t know if any of them are great mics, I don’t know about their noise floor characteristics. And by “noise floor”, I mean how much hiss you have in the background. If you start to bring the gain up, does it start to sound really like… Top heavy? I really don’t know anything about those USB mics, unfortunately, I’ve never used any. But there’s a great website if you guys haven’t talked about it, I’m sorry, I don’t know if you haven’t or not, but it’s called recordinghacks.com and those guys are amazing at testing all sorts of different microphones. And they have ratings on there, they have a really good community forum for questions. They’ve reviewed just about every microphone ever made. It’s called recordinghacks.com, great guys.

HBA: That’s just http: //recordinghacks.com, I don’t know if that’s gonna come through on the screen or not for folks. Oh wow, first thing that came through is “iOxboom iPad Mounting System Review” and it’s got a picture of five different mics, so. I guess it works!

TM: Way to go!

HBA: Yeah I just did an article. I don’t own it yet, but RØDE just came out with the RØDE NT-USB microphone.

TM: Correct.

HBA: I would love to get my hands one. But you’re right about the hiss, that high level or the high end noise that I have not yet heard a USB mic that doesn’t have that. So that’ll be a good breakthrough, if they can fix that.

TM: Well, there are too many problems there and I don’t wanna get too down the rabbit hole on that, but there’s problems with the basic premise of USB as a power supply for a microphone, because the type of switching power supplies that are in computers that supply the power line for USB is a noisy sort of power. It’s going to introduce a lot of harmonically-relative distortion into the line. So I don’t know how they have it filtered on the back end, but I would imagine USB is always gonna have a worse noise floor than something else. So just think about that. I mean, for most things, people who are recording podcasts and stuff like that, it’s probably fine. If you’re just using it to get ideas down, whatever. But if you’re trying to make something that stands the test of time, I would recommend against it. [chuckle]

HBA: Good advice.

HBA: Well, moving on from the gear on the tracking and what would be your advice on the same person, the artist, the person who is recording their own music, doing the tracking, and then the mixing, and then the mastering themselves?

TM: I mean, this is going to sound incredibly self-serving, I’m not trying to sell my own services here [editor’s note: his services are” Liquid Mastering – http://liquidmastering.com/]. I am saying this as an engineer as well who has made the mistake of trying to master his own mixes. I highly recommend that you go to someone else for the final mastering. Somebody you trust, somebody that you know is going to be a competent mastering engineer. They could be another studio in town or something like that, they could be somebody that you find online that you like their catalog. But having another set of ears on the final take of what you’ve got is, I can’t even put a price sticker on it, it’s invaluable as feedback, and every time I’ve… I mean I’ve had a really lucky time. I’ve got to work with some amazing mastering engineers that have done some really top level work and the feedback that those guys had given me at the time was foundationally, just a sea-change in my attitude towards what I was doing. It really helped give me feedback for the next recordings that I was doing, and my own music.

TM: I’ve been in a bunch of bands and recorded and mixed, and tried to master it as well, so I’m familiar with that, and I just recommend against it. Recording and mixing, you can do a lot in that because the lines of that have started to blur, because working in the mix while they’re recording new things, so that can kinda go hand in hand. And then, once you’re doing a real mix on it, it’s nice to play that on as many different playback systems as you possible can. Play it on a laptop speaker, play it in headphones that go in your ear holes, play it on over the ear headphones, play it in somebody’s crappy old Chevy. Just hear what it sounds like on as many different speaker systems as possible, because that’s gonna give you some real world feedback on how your mix is translated.

TM: And that’s the biggest, biggest hurdle to jump over, is how is your mix translating to the outside world? And that biggest difference between people that are doing this just for the fun of it, and people who are trying to release art, and go on tour and make a living doing the music thing, is that they really care enough to check all that stuff. So, it really depends on your means too, there’s no right answer, it’s just I would recommend getting some outside opinion, and listening yourself, before you even go to that outside opinion, on as many different systems as possible, because there’s just so many variables in whatever system you’ve got. If you’re working on headphones, if you’re working on some little speakers on a desk in your living room, whatever it is that you’re doing, you’re only hearing through the lens of what those transducers are producing for you.

TM: So, if you’re mixing without a subwoofer for example, you might be missing a whole two octaves of content, below 80 hertz, that’s just not there for you to be able to notice what’s happening down there in your really low end. And going to systems that have that, can really show you like, “Whoa, my low end is way out of control.” Or, “Where did it go? There’s no low end there.” So, and mid-range issues, mid-range is where most of music of happens. So, really paying attention to, everybody’s got a different bracket of what they consider mid-range, but I consider anything between 350 and up to about 6K is like your mid-range. The human hearing spectrum, I don’t if you’ve ever talked about that, but our ears are the most sensitive around 1 kilohertz, so everything around that, between 1 and 6 kilohertz is the intelligibility factor of all music. So, if you’ve got problems in that range, that’s the first thing to address.

HBA: The baby cry, yeah.

TM: Yeah. [chuckle]

HBA: That’s where babies cry, yeah, we’re so sensitive to it there.

TM: Yeah, it’s which came first, the baby’s cry or we’re sensitive to it because they cry? Who knows? But that’s where the important stuff is happening. And a lot of the main emotional part of music happens in that section. You can do some really fun stuff down in the low end, and you could do some really sparkly beautiful stuff in the high end, but if that mid-range isn’t gluing together, your chances of you emotionally impacting your listeners is difficult. You’ve added more hurdles to your game, so I don’t know what else to say.

HBA: No, that’s awesome, in fact, I’m gonna actually move into a mastering question now, to sort of jump off of that. If somebody sends you the mixed down, because for those of you who may not know this, the mastering engineer typically receives an already mixed down stereo file. So, they can’t go in and just lower specific sounds on tracks, like you can when you’re mixing. So, if somebody sends you a track to master, and they’ve got all kinds of stuff stepping on each other in the mid-range, masking each other, what can you do at that point when you’ve only got the stereo file to work with?

TM: It is very interesting, I’ve been surprised at some of the cool things I could do, even when I wish, where I could have gone back to the mix stage and had them fix it. It’s a combination of different things, using EQ, lot’s of different types of EQ to pull out or abolish different frequencies that are not working well together. Dynamics control, either transients, making sure things in the mid-range that are really bonky, sticking out, stay a little bit more mellow. Multiband compression can really help doing… There’s so many great tools now, it’s unbelievable.

TM: There are some really amazing digital tools that I recommend to a lot of people. They’re not very well known, but they make some of the pure digital plugins, that aren’t trying to emulate an analog classic. Guys write code that is exactly what should be there for the digital world, called FabFilter. I don’t know if you guys have experienced them, I think they’re a Swedish company. Check ’em out, they make some of the best, it’s F-A-B filter, FabFilter. And they make stuff, that is just mindbogglingly cool, and easy to use, beautiful to look at. I use a lot of their stuff for all sorts of crazy different reasons. I don’t know, there’s just so many great tools now. I use a lot of analog things, I use a lot of tube gear.

TM: Tubes imparts this really neat kind of smoothing distortion, it’s really hard to explain. Once you get to know tube gear long enough, you’ll start to hear it, and you’ll be like, “Oh, that’s what I want, that right there.” But tubes really do things… Distortion, I know it sounds weird, because when people think of distortion, they think of like a guitar pedal or something going “waaa”, but creative use of harmonically-relative distortion can really smooth things out. And there’s a whole world of that out there, and I don’t wanna drop a bomb on your viewers, but just play around with different kinds of distortion.

TM: Different type of harmonic distortions, like triode and pentode distortions that happen in tubes, each one imparts different kinds of harmonic overtones and… Having so many great things that you can do but that’s on my side of the fence. In the mastering world, I deal with a lot of different kinds of things depending on what people are handing to me, I’ll reach for different tools. It’s analogy to doing fine woodworking, somebody who’s building a cabinet or something, and then the mastering engineers, the one who comes through and smooths out all those little divots and cracks and crevices, and just polishes everything, and makes it as tight as it can look sort of thing. So it depends, whatever people are handing me, I’ll do different treatments. I don’t think I’ve ever done the exact same thing on two songs. So… I mean, I might have a similar initial approach, but every song is asking for some different kind of thing to make it sound the best that it can sound, and that’s really what mastering is all about, is making the song sound as good as it can, on as many different kinds of playback systems as it’ll ever be heard on. And it’s a pretty amazing feat to try to think about when you’re doing something, is be like, “What is this gonna sound like when they’re listening to it on the international space station?” or whatever. So, anyway. [laughter]

HBA: Yeah, I always take the pre-mastering, my own sort of – I call them “test mixes” – but just take them into the iPod and onto a CD and listen to them in the car, downstairs, on the big consumer speakers, and like you said, in the headphones, in the ear buds, and everything else. And if it passes all of those tests and I don’t have any notes, then I have my wife (Lisa Theriot) listen. She’s also a musician and always hears something I don’t. And together we can usually combine our OCD-like tendencies to the critical listening and at least make sure things sound good on every device before we send the mixes in for mastering. But those mixes are going to have ZERO compression on them from the master bus or as a mixed down file. And I try to leave plenty of headroom by picking a maximum peak of, say, -6 or -6 dB.

HBA: Right. What was I saying? Oh yeah. I was gonna ask you a question… Loudness! Yes. On average loudness level measurements, I always was taught that RMS, root mean square was the standard to use for measuring loudness and for comparing loudness. Has that changed?

TM: Yes. As an industry-wide standard, yes, but it is the closest approximation for a meter. If you’re talking about a meter graph showing you levels, it is the closest approximation to what our ears hear as loudness, but there’s so many psychoacoustic things going on inside of our brain; it’s a really interesting philosophical question when you dive down it. But in the last couple of years, the Audio Engineering Society, AES, has come out with a couple of different standards that have started to be adopted, specifically in the broadcast world. Because they were having so many problems with different levels, from one TV show to a commercial kind of thing. You guys have probably all seen it, where you’re watching a TV show and, you’ve got it up to a certain level to hear the dialog of the show, and then a commercial comes on and it’s just, “Sunday, Sunday, Sunday!” [laughter]

TM: Oh, my God! So, what they’ve done is they’ve established a new standard of… It’s a whole bunch of call letters, but it’s 1773-whatever it is now, and really, what it’s talking about is based off of a peak maximum of 0 dB full scale, which all digital recording is based off of, in that loudness metering scale, the average broadcast now is set up to be operating at 23 dB below that. So, that’s your average level, so they’re not gonna allow much range around that anymore.

TM: But in the music world, there are no standards. That’s part of the problem right now is that everybody, for the last 15 years has wanted… Well, for the last 50 or 60 years has wanted the loudest record possible. And really, back in 2002 was when I really started to notice problems, I was going, “What’s happening here?” Everything just keeps getting pushed up and pushed up and then all of a sudden it’s like the screen right here, the audio waveforms are just, they’re like, get right up to it and there’s nowhere for them to go. And you lose dynamic punch and you add all this ear fatigue because all those waveforms are being clipped almost, and that adds in all these non-pleasant distortion characteristics… That’s one of the things I talk to my clients about all the time is dynamic range. Let’s leave some, because music is meant to be dynamic, there’s no reason to be loud anymore. As a matter of fact, Bob Katz, who’s a mastering engineer I respect a lot, he published a big article last year about how the loudness war is over, because iTunes inadvertently set up this whole sound check system, I don’t know if you’ve seen it in your iPod, but it just comes stock in every iPhone, iPod, Macintosh computer, and iTunes from Windows.

TM: Unless somebody goes in to change the settings, there’s this little box called “sound check on” and what it does is, it goes through and it checks based off of a loudness variable, an algorithm that Apple set up to find the average level of each file that it’s gonna play back, so that if you put Billie Holiday, and The Cars, and Janice Joplin, and Jay-Z into the same playlist, it will keep them at a relatively consistent volume for you. So, there’s no reason to make your track that much louder than anything else, ’cause most people are listening to music on things like iPods and iPhones, and through streaming services like Spotify, and iTunes Radio, and Pandora. So, they all have their own little loudness checks that tries to make the songs closer to each other’s value. And if you over-compress your songs, it actually turns your song down more, and it makes your song sound smaller. So, it’s better to leave more dynamic range and allow your music to have loud sections and quiet sections, and whatever it needs to deliver its emotional content.

TM: But as far as RMS, sorry to get so tangential, RMS is a good way to meter for loudness, but it’s not going to tell you exactly what’s going on as far as a human being is going to be able to understand that loudness. Because the way that our ears convert the frequencies hitting them into signals that our brain can interpret, and then how our brain interprets those signals, an amazing mystery box of all sorts of different sorts of things happening. And so, to just have a loudness meter at all is a… It’s kind of like throwing a dart, you’re getting close, you’re saying, “Okay, I think I’m sort of like this loud,” but really it comes more down to dynamic range. Our ears are so much more sensitive to dynamic range. For example, in the human ear… There’s lots of different theories out there, but one of the most recognized theories about the way that we hear is that we have 24 discreet jumps in doubling of volume that our ears can hear. So, you double it once, double it again, double it again, double it again, we can do that 24 times.

TM: Our ears can hear the smallest fly’s wings beating across the room, and you can stand next to a giant jet airplane and hear all the swirly craziness in the engine. And the level of difference in those pressure levels is gigantic, and a magnitude of 24 is what we can hear. But in pitch, in frequency, we can only hear 10 octaves, which are doubling of frequency. We’ve only got 20 hertz to 20 kilohertz and most people don’t even have 20 kilohertz. So, we have a drastic amount of frequencies, but we have a whole lot of dynamic ranges, so let’s leave a lot of dynamics, our music will sound better with dynamics.

HBA: When I sent in my master… Well, my master, I shouldn’t use that word. When I sent in the final mixes to the mastering engineer this last go, one of my songs had… It was on a previously recorded compilation that wasn’t mine. And so, that was… I did not have the original tracks. I only had that final, already mastered version in with the rest of the songs. So, I tried to leave everything at… I was using RMS to try and leave a certain amount of room below. I don’t remember how much I decided on, but leave enough head room below 0dB for there to be room to work with.

HBA: And when I mentioned to the mastering engineer that this one song had already been previously mastered, I didn’t… I wanted him to take from that that this doesn’t need much in the way of dynamics. Just make it the same loudness as what everything else ends up being. And he took that to mean that all the other songs need to be brought down to the level of that one song. And when I got the master back, I was horrified. And then, I was like, “Oh, my God. Oh, my God. Oh, my God!” And he said, “Hey, if you tell a mastering engineer that one of the songs on your collection has already been mastered, they’re gonna use that as the reference.” And so, that was a lesson learned.

TM: I wouldn’t take… I mean, that wouldn’t be my approach.

HBA: Oh, good. Then we’ll have you master our stuff next timeJ.

TM: Engineers are people, too, and we’re… All sound engineers are very opinionated and we’re all right. [laughter]. I just… When somebody brings me something like that and if they say this track has already been mastered, I’ll say, “Well, are you happy with the mastering job on that track? Do you want the other songs to feel more like this master or do you want me to do what I do and that one just gets the same treatment, and they all up sounding a little bit more like each other, or what?” So, I would try to clarify upfront with you what you wanted from that mastered file, because just because something has been mastered doesn’t mean it can’t be treated again. I mean, as a matter of fact, the same song can be mastered 10 times for different releases in a movie soundtrack and in a TV show and without vocals for a commercial or whatever. So, the same song might be treated differently for a lot of different kinds of releases. So, there’s nothing wrong with re-mastering a track as long as you’re starting with good source material. It really doesn’t matter.

HBA: Okay. I am gonna ask, I think, one more question. But then, I’d like to hear if you wanted to talk about Liquid Mastering.

TM: Oh, I love mastering. It’s what I wanna do when I grow up. [laughter]

HBA: How does one become… How does one make the leap that… It’s always, I’ve been reading Recording Magazine since it came out. In fact, it wasn’t even called Recording Magazine back then. And there’s always this sort of secrecy, this hush, this sort of sense of awe and mystery that surrounds mastering. And I always wondered, why, is there a secret? Is there a secret handshake? Do you have to… Are they… Do they have some secret tools that they don’t want anyone else to know about, or is it just a matter of, you really have to have hyper-developed ears, lots of experience, and if you can, maybe some formal training?

TM: Yeah, I would say all of that. There’s no secret handshake. I don’t think I’m cool enough to know it anyway. [laughter] But really, what it comes down to is attention to detail. And mastering engineers are a special breed of people who are most of the time, not happy with settling for anything less than the top 10% of what is capable, and sometimes the top 1% in some cases. Mastering equipment, it usually costs upwards of four to 10 times more than the same sort of thing that you’d get for a recording because of the fine point controls that are needed. One of the things that, once I started getting into mastering more, was being able to recall settings. And with a lot of recording gear, it’s made to just go as things need to be done. You bring this level up. You turn this dial. And “Okay, that’s great. That sounded good for that song. What are we doing now? We’ll just change this around and make this next song sound good.”

TM: But with mastering, you have to be able to recall settings. You have to be able to say, “On this song, this processing was done.” And then, if somebody wants you to reprocess that with a different kind of approach, you can reset all of that to the same settings, which in the digital world, that’s pretty simple now, because automation lets you just take a snapshot of where everything is. But if you’re working an analog equipment, the ability to have that snapshot recallability by having detented pots and things like that, it costs a lot more money. Plus, the R&D that goes into the backend of really good mastering equipment is far greater than that that most people can afford to buy for a recording and et cetera. So, really, what you’re paying for when you’re buying higher levels of gear is more people hours, man or woman, attention to what is going into making that signal sound good, signal treatment.

TM: And crossing the barrier into mastering can be an expensive prospect because you need to buy better gear, you need to have great speakers, you need to have a really nice tuned room, you need to have a room that does not impart too much gunk, because walls are just a constant problem. This room that I’m in right now, it’s not the room that I prefer to work in, it’s more of my editing suite. Every room is going to impart a certain kind of characteristic, and having a really, really good room with a flat response and with not a whole lot of decay and not a whole lot of absorption, having a nice balance between absorption and reflection in a room, it’s expensive as well; to build a good mastering room, it’s a whole big game. So, jumping into mastering, if you wanna do it for real, you have to invest a lot of yourself, not just money, but time, learning how to do the kinds of things that are required for the different formats.

TM: For example, mastering for vinyl is a completely different process than mastering for CD or an online release. And back in the day, when tapes were in vogue and you had to put something to a tape, that would need its own processing. So, really, it’s all of those things. It takes years of experience to understand the finer points of all those different things because EQ is EQ is EQ. But depending on what your doing at each stage, if your EQing for a tracking thing, you’re going to approach it one way. If your EQing for a mixing thing, you’re going to approach it another way. And then that same kind of EQ, it will probably be a different box, but that same kind of EQ, what’s doing boosting or cutting, or shelving, or tilting, or whatever it is that you’re doing, it’s going to be for a very specific and different outcome.

TM: So, the reasons behind each of those stages are very different. And it’s hard to say, I can’t not give away tricks, because the tricks that I do might not work for you. Each person who gets into the field has a different approach about what they think is going to get to the end goal, and there’s a lot of similarities. When you get to a mastering engineer, we all do a very similar job of approaching the song, because we know when we hear a song, we go, “Okay, we know that this needs to happen and this needs to happen.” And a lot of the equipment that we use is built for the same sort of purposes. So, a lot of mastering engineers end up having a very similar conversation about things, because really, it’s like, “Oh, okay, I see what needs to happen there for that song to stand out,” or “You know what? There’s just way to much 500 hertz on that verse. I just need to bring down that one frequency a little bit, and that’s going to sound great. And this has been the biggest lesson for me, really good mastering engineers know when to do nothing. [laughter]

TM: Knowing when to do nothing is a big step in your achievement. You can be like, “You know what? This song sounds really good. I’m going to leave it alone, and I’m going to let it be what it is, and then come back to it once I have everything else. And then maybe dynamically, it needs to shift a little bit better to fit to the whole record.” But it really depends, if I’m mastering a single, if it’s gonna be on iTunes, or if it’s gonna be on a vinyl disk, every approach is gonna be different. So, I can’t really tell you, “Oh, here’s the secret to that.” It’s just getting it to sound the best that it can for the output medium is the goal. Sorry, if that’s too long-winded, everybody.

HBA: No. There were a lot of awesome nuggets in that one. Yeah, that’s great. Well, one last thing that I wanted to ask you about is if you had wanted to sort of plug what you’re doing in Liquid Mastering.

TM: Oh, yeah, I mean, check out what I have built on Liquid Mastering. There’s a lot of different forms of music and some of it needs updating, it’s years old now, but it just gives you an idea of what my approach to mastering is. You can see a version side by side on my player of what file somebody gave to me to start with and what I ended up giving them back, and… I love what I do. Every client I work with, I try to work with until they’re happy. Some people, you can’t please them, but most of my clients are great, and I love their music, and I get into what they’re doing, and I follow their career afterwards. I’ve been lucky to meet some really amazing people through it, and I’m doing music from around the world. I love what I do. I want to do more. Let me check our your music, send me some of what you’re up to, I’d love to hear it.

HBA: I will most definitely do that. And I’ve put the link there, I don’t know if it’s showing up on yours, it should show up on the final broadcast there, but it’s, “Your last stop in great sounding recordings,” does that sound familiar?

TM: Yep, liquidmastering.com.

HBA: And there it is on the screen there and in case you missed it, it’s simply liquidmastering.com. So, if you’re working on a project or you have a project coming up, I highly recommend that you send your product out for mastering, and yeah, contact Liquid Mastering, and… Can you, will you send people, if they send you a song and say, “How much would it be to do one song so I can hear what you do,” or is that just something…

TM: Yeah, I mean there’s been times that I’ve worked out things with people to do a trial run to see if I’m in the right fit, but also, I might be able to hear something and know that I’m not gonna be the person that’s gonna be able to help you, or you might need to go back to the mix stage and adjust some things. But usually, I don’t like doing work without having some sort of an established communication or understanding that we’re gonna move forward on something. Because my time is valuable just like yours is, and I like having the respect of a mutual exchange. I respect your music. You respect my need to make a living. [laughter] So, I’m willing to work with people on what they have, and I’ve done plenty of times, checking people’s music out and giving them feedback on how they could affect their mix better before it comes to the mastering stage. I’m happy to do that, but taking the time to do mastering, it’s kind of a commitment, so it’s hard to do too much of that on spec. It’s an investment of time, energy, and a lot of focus, so it’s hard to do that without having an established agreement with people that we’re gonna be able to move forward together on a project. And… You know what I mean?

HBA: Yeah, I was gonna say that your description of the service you provide is already better than what I experienced on my last project, because I could not… There was no relationship. There was no clarification of what I wanted. There was no give and take. It was just boom!

TM: Yeah, the mastering engineer should be a person who’s giving you feedback, if you want it, on what you’re doing, from another person’s point of view. And not to say that they’re right, but they can at least give you a different point of view, so whether you take it and run with it, or you say, “Wow, that guy’s an idiot. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” Just having another point of view gives you some way to think about your music that you’ve never thought about before. So, I think that’s hugely valuable. That’s the way I approach it. Some mastering engineers like to completely be hidden, never talk to anybody ever, complete social recluses, and there’s some value in that, too, but that’s just not who I am and how I work. [laughter]

HBA: That’s fantastic. Alright, that’s pretty much all the time we have. This has been incredibly awesome, Thaddeus. I thank you so much.

TM: Sure. Absolutely. I’m glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

HBA: Oh, yeah, thank you. And this, for everybody else, will be available on YouTube for people to watch later. (that link is: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=20nX6Iiq4GA And any parting words for us, Thaddeus?

TM: Just make the best music you can, and please go research the difference between lossless and lossy audio codecs. Just remember those terms, lossless and lossy. We didn’t get time to talk about it, but it’s a really important thing and everybody should learn about it.

HBA: Got it. I will make another note to myself to do a post on lossless versus lossy format, so that’ll help amplify your message. Well, alright. I will let you get back to your evening, and once again, I very much appreciate it, and hopefully, we can maybe do some work together in the future with the next album.

TM: That’d be great. I’d love to hear it.

HBA: Alright. Well, thanks again, and I’m gonna stop the broadcast now. See you later, everybody.

Interview With Mastering Engineer – Thaddeus Moore

Last night I had the pleasure of interviewing Thaddeus Moore, who is the lead mastering engineer for Liquid Mastering. We talked for an hour audio recording, mixing and mastering, and Thaddeus shared his thoughts on the best way to do (or not to do:)) these things in a home recording studio. We also get some great insights into what mastering actually is, and why it is advisable – if at all possible – to have your songs mastered by someone OTHER than you:).

Last night I had the pleasure of interviewing Thaddeus Moore, who is the lead mastering engineer for Liquid Mastering. We talked for an hour audio recording, mixing and mastering, and Thaddeus shared his thoughts on the best way to do (or not to do:)) these things in a home recording studio. We also get some great insights into what mastering actually is, and why it is advisable – if at all possible – to have your songs mastered by someone OTHER than you:).

We did this interview using Google Hangouts On Air, which creates a video of the event and places that video onto our YouTube Channel. This is excellent news for a number of reasons. First, it allows folks who could not attend the live interview to see the entire thing when it is convenient for them. And 2nd, it allows us to go back and watch multiple times so we don’t miss anything! I just watched the first 5 minutes again and was reminded of some important things I’d already forgotten! There is gold here if you want to improve you music recording and producing skills.

One of the most interesting answers Thaddeus gave was to my question asking for a piece of over-arching advice for recording musicians or folks hoping to get into recording their songs. He said that more important even than gear or production techniques is the song itself! “The best thing that you can do focus on content in your writing and compositions. There’s no better gear for a song than a good song.” I bet you would not have guessed something like that would be at the very top of his list!

There’s no better gear for a song than a good song.

I’m going to have the interview transcribed so I can put everything into words. But that will take a few days. So until then, you can watch the replay at your leisure below or over at our YouTube Channel here: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEoaZXqy26HigFAmAuO7vCA