EQ…That Thing You Never Knew Quite How To Use

EQ…That Thing You Never Knew Quite How To Use

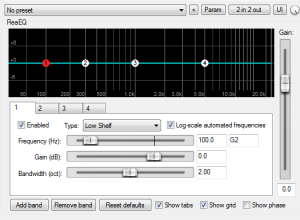

Have you ever seen one of these things? They used to be common in “entertainment systems.” Right along with your CD Player, Cassette Player, Record Player, amplifier, and “tuner” (meaning…”radio”), would be this other big boxy thing with nothing but a row like 30 vertical (meaning “uppy-downy”) slider controls across the face of it.

These sliders had little square button-like thingies that you could slide up or down. They usually started out in the middle (at the “zero” mark). About the only thing they seemed good for is making funny patterns, like smiley faces, or mountain ranges, by moving the sliders up or down in the right way. Besides maybe making you feel better by having your stereo “smile” at you, I really don’t think anybody ever knew what to do with one of these things.

But it sounds scary

With a scary name like “graphic equalizer,” it sounded so important. It also sounded like a good name for a “rated-R” action movie, but that’s another story. Anyway, you had to make everyone think you knew why you had one, so you pretended to know what it did. But in reality, you felt safer just leaving it alone to sit there with its straight row of slider buttons right down the center, the way it was the day you brought it home because it came with all the other stuff.

You are probably familiar with some kinds of EQ without realizing it. You know those controls on your music player labeled “bass” and “treble”?” That’s a crude EQ! If your graphic EQ box had only 2 little sliders on it, it would be the same thing. One control makes the sound “bassier” (the low sounds) and the other makes the sound “treblier” (the high sounds).

I always laugh when I see someone turn both controls all the way up or down. They have accomplished absolutely nothing that the volume knob wouldn’t do. If both (all) the sliders are up, you just turned the radio up. Congratulations. An EQ is only useful if you can make shapes OTHER than straight lines with the sliders.

So now you’re wondering what the heck an EQ IS good for aren’t you? Well for one thing, it turns out that our ears lie to us! Can you believe it? I know! It’s crazy, right? Every human has lying ears. I was floored when I first heard.

It turns out that there are all kinds of sounds out there in the world that we can’t hear! As a matter of fact, MOST sounds are inaudible to humans. The only sounds humans CAN hear are those in the range between 20 hertz (abbreviated as “Hz”) and 20,000 Hz. A “hertz” is a measure of how often (or “frequently”) something shakes back and forth (or “vibrates”) in one second. See the video below.

Sound is just energy that makes air particles shake back-and-forth. When these air particles vibrate with a frequency of between 20 times and 20-thousand times per second, it makes a sound that is in the “range of human hearing.” Though if you’re 21 or older, good luck hearing things above 16,000 Hz;) (where the so called “teen buzz” or “mosquito frequency” lives. Confused? Ask a teenager.

Some Particular Sounds Are On the Same Predictable Place On The Frequency Spectrum

In the frequency spectrum between 20-20 thousand Hz (usually abbreviated as “KHz”), some amazing things happen.

One interesting example is that a baby’s cry is at perhaps the most annoying frequency there is, around 3KHz. I say “annoying” because humans are MOST sensitive to sounds at that frequency.

This may be a survival thing for us. But since we don’t usually have a “crying baby” solo in our audio recordings, why is this helpful?

What that means is that everything we can hear vibrates around certain predictable frequencies. And knowing that gives us some pretty cool superpowers.

For example, I know just where to find the signal of a bass guitar on the spectrum. It’ll be down around the low frequencies of 80-100 Hz. So will the kick drum. The electric guitar will usually be in the mid-range between 500Hz and 1KHz in the upper mid-range along with keyboards, violas and acoustic guitars and human voices. Clarinets, violins, and harmonica’s tend to hang out mainly in the upper-mid range around 2-5 KHz, and things like cymbals, castanets, and tambourines like to be in the “highs’ up around the 6 KHz.

Just ignore the fact that, in a range that tops out at 20KHz, we call things at 7 or 8 KHz “highs.” It’s because the spectrum is exponential, and not linear. If that makes your brain hurt just ignore it. It’s sometimes better that way.

Now that we know where specific things live in the range of hearing, we can adjust volumes at JUST those frequencies without affecting the rest of the audio.

Knowledge of this “range of human hearing,” and how to use (or NOT use) an EQ will come in handy more often than almost any knowledge. Once we know where to quickly find where a sound is on the EQ spectrum, we can surgically enhance, remove, or otherwise shape sounds at JUST their own frequencies, without affecting other sounds at other frequencies.

But how in the world can we adjust volume in just one narrow frequency, say 100 Hz, without also changing the volume at all the frequencies? Hmm, wasn’t there some discussion about a thing called an “EQ” that had a whole bunch of sliders on it? Could it be that those sliders were located as specific frequencies, and could turn the volume up or down just at those frequencies without affecting the rest of the sound? Why, yes. It could be. Now you know.

This video is an excerpt from The Newbies Guide To Audio Recording Awesomeness 1: The Basics With Audacity, and should really help you understand all this stuff better. It breaks things down to the simplest basics – and might even make you laugh a little:-).

Mixing With EQ Instead of Volume Controls

Once you know where the frequencies of certain instruments are likely to live, you can use an EQ to prevent these sounds from stepping all over each other in a mix and sounding like a jumbled mess, with bass guitar covering the sound of a kick-drum, or the keyboard drowning out the guitar. “But you wouldn’t need to use an EQ to do this if you use a ‘multi-track’ recorder, right?” That’s what recording engineers and producers usually use to record bands, and other musical acts, so each instrument and voice is recorded onto their very own “track.” Since every different sound has their own volume control, it seems obvious what to do if something is too loud or quiet, right? ‘Don’t you just simply use a mixer to turn the “too loud” track down, and vice versa. I mean, isn’t that what “mixing” means?’ That’s what I used to think too. The answer is… “only sometimes.” For example, even after spending hours mixing a song one day, I simply could NOT hear the harmonies over the other instruments unless I turned them up so loud that they sounded way out-of-balance with the lead vocal. It was like a bad arcade game. There was simply no volume I could find for the harmonies that was “right.” It was either lost in the crowd of other sounds, or it was too loud in the mix.

Then I learned about the best use of EQ, which is to “shape” different sounds so that they don’t live in the same, over-crowded small car. Let’s say you have one really, really fat guy and one skinny guy trying to fit into the back seat of a Volkswagen Bug. There is only enough room for 2 average-sized people, and the fat guy takes up the space of both of those average people already. Somebody is going to be sitting on TOP of someone else! If the fat guy is sitting on the skinny guy, Jack Spratt disappears almost completely. If Jack sits on top of Fat Albert, he will be shoved into the ceiling, have no way to put a seatbelt on, it’s just all kinds of ugly no matter which way you shove ’em in.

But if I had a “People Equalizer” (PE?), I could use it to “shape” Albert’s girth, scooping away fat until he fit nicely into one side of the seat, making plenty of room for Jack. Then if I wanted to, I could shape Jack a bit in the other direction, maybe some padding to his bony arse so he could more comfortably sit in his seat. Jack just played the role of the “harmonies” from my earlier mixing disaster. Albert was the acoustic guitar. Just trying to “mix” the track volumes in my song was like moving Jack and Albert around in the back seat. There was no right answer. But knowing that skinny guys who sing harmony usually take up space primarily between 500 and 3,000 Hz, while fat guitar players can take up a huge space between 100 and 5,000 hertz, I can afford to slim the guitar down by scooping some of it out between, say, 1-2KHz, and then push the harmonies through that hole I just made by boosting its EQ in the same spot (1-2 KHz). Nobody would be able to tell that there was any piece of the guitar sound missing because there was so much of it left over that it could still be heard just fine. But now, so can the harmonies…because we gave them their own space! And we did all this without even touching the volume controls on the mixer. So it turns out the EQ does have it’s uses!

Cheers!

Ken

Post-reverb compression

Post-reverb compression Here’s a tip to help you record and finish long voice over jobs more efficiently (which translates to much faster). If you are lucky enough to have gotten a fairly long voice-over job, such as an audio book, documentary narration, etc., then you know that there will be little mess-ups along the way that need to be fixed at some point. There are a few ways to deal with that.

Here’s a tip to help you record and finish long voice over jobs more efficiently (which translates to much faster). If you are lucky enough to have gotten a fairly long voice-over job, such as an audio book, documentary narration, etc., then you know that there will be little mess-ups along the way that need to be fixed at some point. There are a few ways to deal with that.

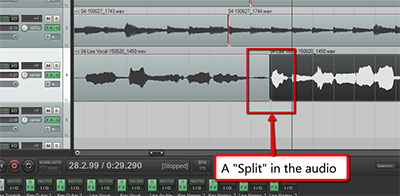

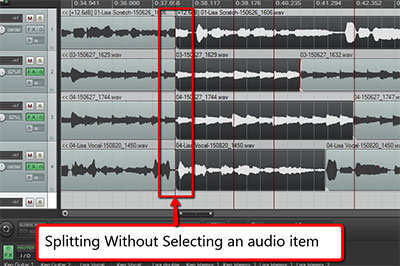

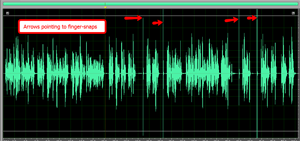

In the picture to the left, you can see where I make the visual cues by snapping my finger close to the mic after a mess-up (no cracks about how often I mess up! That’s not the point;)). Compared to my voice narration, these quick snap or crack sounds stand out like a sore thumb. Now I can simply zoom into each mistake and delete both the snap sound and the mistake. It took me all of about 45 seconds to do that for all 4 edit-points in the job to the left.

In the picture to the left, you can see where I make the visual cues by snapping my finger close to the mic after a mess-up (no cracks about how often I mess up! That’s not the point;)). Compared to my voice narration, these quick snap or crack sounds stand out like a sore thumb. Now I can simply zoom into each mistake and delete both the snap sound and the mistake. It took me all of about 45 seconds to do that for all 4 edit-points in the job to the left.