I received an e-mail yesterday from someone in country rock band who wanted to augment their live performances with instruments they don’t typically have for live shows, such as fiddle and banjo. He has the midi files for the parts already. The problem is that the instrument sounds being played by the midi tracks for fiddle and banjo sound really cheesy and cheap. That’s because his recording software, Apple’s GarageBand, comes with some low-end synthesized instrument sounds built in.

He needed more realistic sounding instruments. Below is the advice I sent him:

Hey Scott,

It sounds like you’re dealing with the joy and wonder of on-board or built-in midi instruments, which are typically very cheesy sounding.

It sounds like you’re dealing with the joy and wonder of on-board or built-in midi instruments, which are typically very cheesy sounding.

To get decent sounds for these instruments in particular you usually have to spend a bit of money. There are free plugins out there but you usually get what you pay for:). Do you have the Apple JamPack Rhythm Section software? There is a banjo in that collection that is sure to sound better than the built-in one. And the pack is pretty affordable at $99.

I have tried many fiddle and guitar sounds and they seem to be among the most difficult sounds to re-create for cheap. I have heard many times that the fiddle AND acoustic guitar sounds in a product called Quantum Leap Gypsy are incredible. I’ve used Quantum Leap sampled drums in just about every recording I’ve made, so I know they are fabulous in general.

Once you have the virtual instruments installed, they will show up as choices on your GarageBand tracks. Just load the midi files and select the appropriate instrument for each part and mix down the result. That should do the trick. Plug your laptop into your sound system and you’ll instantly add new band members for your live performances. Another bonus is that they don’t drink beer;).

See an earlier Home Brew Audio article on virtual instruments here: https://www.homebrewaudio.com/home-music-studio-awesomeness-virtual-instruments

Cheers!

Ken

Recording Tips and Techniques

Quickly Turn One Long Audio File Into Many Small Ones

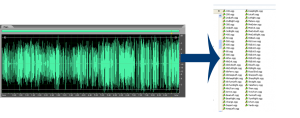

You can break up a single long audio file into several smaller files very easily using an audio editing program such as Adobe Audition. Other programs may have other ways of doing the same thing, but this article will focus on the tools in Audition. So are you ready to save a little life? Read on.

If you work with audio on your PC recording studio, you will, at some point, almost certainly need to take one long section of audio and convert it into lots of smaller sections of audio. This task usually involves giving each small audio file a unique name. The first time I was presented with this job I couldn’t think of any was to do it that didn’t involve repeatedly cutting several seconds of audio from the main file, pasting it into a new audio file, and then using the “Save As” function to give that little piece of audio the appropriate file name. Gahh! That may not sound bad when you’re talking about converting a 1-minute long sound file and saving it as 4 or 5 smaller ones. But when you are presented with 45 minutes of contiguous audio, and the final project requires over 100 small audio files, well it quickly becomes apparent that it IS bad. That is unless you can find a better way to do it than the “cut-paste-Save As” technique done 100 times.

Fear not, intrepid audio recording ninja! Your weapon of choice is Adobe Audition. Here is how you can accomplish what would have been a long and tedious task in just a matter of minutes.

Step 1. Open your audio file in Audition.

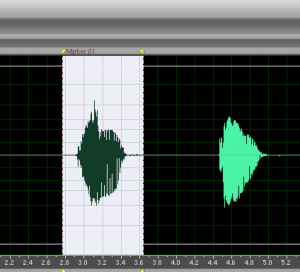

Step 2. Select the first bit of audio that will need to be saved as its own file by dragging the cursor over it.

Step 3. Hit the “F8” key on your computer keyboard. This will create a phrase marker for the audio you selected. See Figure 1.

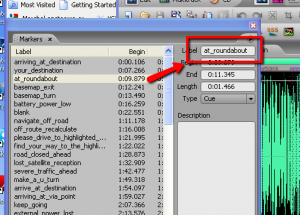

Step 4. On the Window drop-down menu, select Marker list. This will open a floating window that shows every marker you create in the long file.

Step 5. Repeat steps 2-3 for the next bit of audio that needs to be saved off as its own file. The process only takes about 5 seconds. Highlight and hit F8; highlight and hit F8.

Step 6. Once you’ve marked off all 100 sections of audio, you’ll have 100 markers showing in your Marker list. Each one will have a window next to it called label. Presumably you will have a document telling you what you should

name each smaller file. Simply copy the target file name and paste it into the label window. See Figure 2.

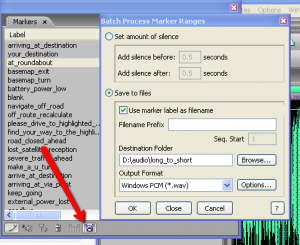

Step 7. After every marker has a label, click on the icon at the bottom of the Marker window for Batch Process Marker Regions. The icon looks like one of those old floppy disks.

Step 8. Select your destination folder and audio file output format (mp3, wav, etc.) and put a tick in the box that says “Use marker label as filename.” Then hit OK (see figure 3). That’s it! Done! Every marked phrase is now its own separate file with the proper file name.

Okay I hear you. Even THAT process was a bit tedious and repetitive. Surely there is a way to automate it even further. Well yes there is, especially if the filenames don’t have to be specific, only unique. For example, if the project calls for 100 small audio files named sound_1.wav, sound_2.wav…sound_100.wav, the process is much shorter. You simply eliminate Step 6 above.

Then all you have to do is remove the check mark from the Use marker label as filename box in the Batch Process Marker Ranges window. You can also specify what the prefix for each filename should be at this point (such as sound_ in the example above). Then each file will be named in sequence.

Do I hear more moaning about automating even more? Sheesh, what a bunch of impatient people you are. OK, there is one other thing you can do. It will require a bit of trial and error, but will be well worth it as long as there is at least a little bit of silence between each bit of audio in the big file.

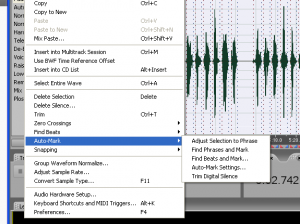

Select enough audio in the big file so that it encompasses 4 or 5 of the smaller phrases. Select Edit/Auto-Mark/Find Phrases and Mark. If you’re lucky, all 4 or 5 of the audio phrases will be marked in one click of a button! You may have to adjust the Auto-Mark settings (see figure 4) for what constitutes signal and silence, etc. But after you get it right, select the entire file and run Find Phrases and Mark. Boom! All 100 sections of audio are marked off in an instant.

Under the right circumstances, using the above steps can turn an hour-long job into a 5-minute job. Now THAT is worth doing, unless you have no better use for your time than to do unnecessary work. Do it with Adobe Audition

Good luck in your audio editing ventures!

Ken

Home Recording Awesomeness-How to Silence The Electric Buzzing

The key to professional sounding audio, especially in home recording situations, is to keep as much noise out of the audio as possible. The less noise (hum, buzz, hiss, lawn mowers, computer drive noise, etc.) you have mixed in with the sound you’re trying to record, the better. Prevention is best. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

The key to professional sounding audio, especially in home recording situations, is to keep as much noise out of the audio as possible. The less noise (hum, buzz, hiss, lawn mowers, computer drive noise, etc.) you have mixed in with the sound you’re trying to record, the better. Prevention is best. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

My computer died recently, and the replacement required me to put a new audio interface the M-Audio Fast Track, into my studio setup. I was getting an awful buzzing through the wires and try as I might I couldn’t get rid of it. It was too loud to remove with audio editing tools, such as noise reduction or gating. I simply had to find and eliminate the

source before I could do any recording.

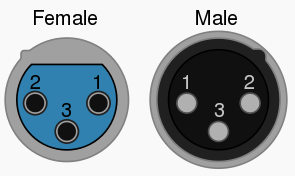

The Fast Track Pro has inputs called “combo connectors” on the front that allow you to plug in either a 1/4-inch cable connector or a 3-pin microphone cable connector (called an XLR connector – see Figure 1). The way I had my previous interface connected was with a regular old 1/4 plug coming from my outboard microphone preamplifier (See Figure 2).

So I thought I could simply replace the old interface box with the new one, keeping the same cable connections. Are we making guesses as to how that turned out for me? “Badly” is the answer. That buzzing I mentioned was coming from or through the new interface. I knew this because it only happened when the interface was turned on. Clever huh?

It turns out that audio gear with amplifiers (like audio interfaces) in them are extremely sensitive to electromagnetic (EM) fields, which basically means that if there are electrons moving around anywhere near this gear, they are likely to flock to it like bees to honey, and create a very similar noise to that same mixed metaphor…buzzing! What causes electrons to fly around your stuff? Electricity is the main culprit. Anything that is plugged in and sucking juice is likely to be the cause of humming or buzzing. So what do you do?

First, check the cables running to and from the interface box. If there are any power cables touching it or its wires, separate them. Just get them the heck away from each other. Pay special attention to proximity to AC adapters, otherwise known as wall warts or power bricks. They cause lots of EM. Picture a big cloud of bees around one of these things. As in real life, steer clear of the bees!

Next, check to see if the wires running to and from the interface are balanced or unbalanced. You can usually tell by looking at the sockets in the gear which will usually say “balanced” or “unbalanced.” Go figure. Another way you can tell is by what kind of connector is at the end of the cable. If it looks like the one in figure 2 (with a single black stripe toward the tip), assume the connection is unbalanced. If the connector looks like those in Figure 3, assume you have a

balanced connection. Don’t worry about understanding what it means for electrical stuff to be balanced or unbalanced. I’ll write an article about that very soon. For now it is enough to know balanced connections can protect against electricky noise. So if your stuff is hooked together by unbalanced cables, check to see if the gear can accept balanced connectors. If so, try swapping your 1/4-inch pluggy cables with XLR ones and see if that doesn’t reduce or eliminate the buzzing noise. In my case it was exactly what was needed!

My old mic preamp (Peavey VMP-2) has two “output” sockets on the back, one with an XLR shape that had the word “balanced” cleverly written by it, and another with a 1/4-inch hole and the word “unbalanced” by it. Cryptic and confusing, no? No.

Anyway, the moral of the story is this. If you are hearing electricky- sounding buzzing or humming coming from your audio gear, try two things right off the bat:

1. Separate the cables as much as you can, and steer especially clear of the ones with big power packs on them.

2. Check to see if your connections are balanced or unbalanced. If unbalanced, try switching to a balanced cable connection. One of these two actions will likely solve or at least greatly improve your noise problem.

Good luck!

Ken

How To Record A Voice Over With Audacity

Here are some suggestions on how to record a voice over. Ready to land your next voice over job?

Here are some suggestions on how to record a voice over. Ready to land your next voice over job?

This is a fairly detailed step-by-step guide for creating a pro quality voice over using Audacity (the free audio software). The steps here will work for any mic, but you should use at least a decent USB mic like the Samson Q2U (which you can get for 59 dollarinis). Ready? Here we go.

1. Open Audacity (you can download that here)

2. Make sure your mic is set up in Audacity

To do that, go to Edit/Preferences/Devices (choose the Samson mic under “Recording” and make sure it says “mono” under “channels.”

3. Click the “Record” button (big red circle) in Audacity – a track will appear and begin recording.

4. Record your voice-over

Here are some tips for that:

- Use a pop filter if you have one. If you don’t, you can make one quickly by stretching an old pair of nylon stockings over a wire hanger that you have shaped into a circle. But you can buy one for about $10 on Amazon – Auray Pop Filter.

- Record in as quiet a place as possible.

- Keep you mouth close to the mic (3-5 inches). Most of us record in spare rooms in our house, which means lots of echo-y, reverb-y room sound. And one quick way to reduce that that you can implement immediately is simply to record close (that 3-5 inches I suggest) to the mic. I believe that this could be the most helpful bit of advice on how to record a voice over of everything in this post.

- Keep recording even in you make a mistake. I like to clap my hand or make some other quick, loud noise after a screw-up so that I’ll see it on the track when I’m editing. Just make that mark and continue recording. You can cut the bad takes out during editing.

- Make sure the wave forms (blue blobs) are fairly large in the track. You don’t want to over do it to where they go out to the edges and beyond. But if they are too quiet – not much more than what’s on the center line – then you should turn up the input level* and start again until you get fat and chunky blobs. This may be the 2nd most important piece of advice for how to record a voice over!

* If you are using an interface unit to plug your mic in, you can turn the input level up on that. If you have a USB mic, go into your Windows Sound control panel, click on the Recording tab, select your mic, select Properties, click the “Recording” tab, and then “Level.” Make sure the slider is at around the 85-90 percent mark. Sometimes Windows puts this level down to like 20% for some reason.

5. Hit the “Stop” button when you’re finished (big yellowish square).

6. Now find all the parts you want to cut out (bad takes, baby crying, phone ringing, etc.) by highlighting that bit of audio and simply hitting the “delete” button on your computer keyboard.

7. Once you’re left with the parts you want to keep, it’s time to reduce the ambient background noise.

8. Find a section of the recording where you’re NOT talking, but the mic was recording. Usually this will be low-level computer drive noise, electronic buzz or hum, etc.

9. Select Effect/Noise Removal in Audacity and select “Get Noise Profile.” The Noise Removal window will close. You’ve just told audacity what constitutes “noise.”

10. Select the entire audio recording (double-click on the audio), open the NR tool again, and click “OK.”

This will filter out the ambient noise and leave your voice alone (for the most part).

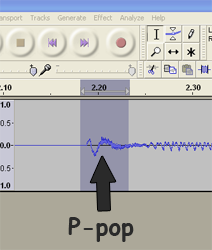

11. Listen carefully to the recording in headphones. You’ll likely have several “p-pops” or “plosives” as they are commonly called.

Zoom in to very beginning of an offensive p-pop (see:

https://www.homebrewaudio.com/how-to-fix-a-p-pop-in-your-audio-with-sound-editing-software for a bit more on this)

12. I find that bad p-pops tend to look like the letter “N” in the audio waveform.

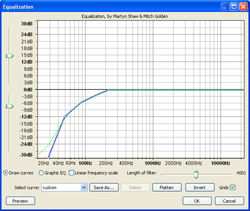

See pic. Select just the “N” part and then go to Effect/Equalization in Audacity.

13. Create a curve on the horizontal line that starts sloping down to the left at about the 200-250 Hz spot.

Just click your mouse on the line wherever you want to create a drag-handle (4 or 5 spaced between 30Hz and 250Hz should do the trick). Then drag the 30Hz handle all the way down.

Drag the next one to the right down but not as far, etc. Continue until your curve looks like the picture above.

14. Then click “OK” and listen to the result.

The “p” sound should sound more natural and less like an explosion of air. You’ll also notice that the “N” shape is much smaller.

15. Next You’ll want to compress the audio just a smidge to even out the volume and give it some punch.

So select the entire audio file (double-click on the blue blob somewhere) and select Effect/Compressor. Set the sliders as follows: Threshold: -12 db, Noise Floor: -40 db, Ratio: 2:1, Attack Time: 0.2 secs, Decay Time: 1.secs.

Also, make sure there is a check in the box marked “Make-up Gain for 0dB after compressing.” Click “OK.”

16. Now listen carefully, through headphones, to all the audio.

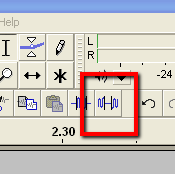

You may notice a few stray bits of unwanted noise in between the talking bits, so to fix those, just highlight them as you find them, and click the “Silence” tool button in Audacity (see Pic 3).

17. Lastly, save the audio in whatever format you need by selecting File/Export in audacity.

44.1KHz and 16-bit wav files are standard “CD quality” audio. Note that if you want to export the audio as mp3, you’ll need to download the Lame MP3 Encoder here: http://audacity.sourceforge.net/help/faq?s=install&item=lame-mp3 . That will install to the correct place automatically.

Hopefully that should give you an idea how to record a voice over, a professional sounding one, very quickly. For more in-depth info, check out our course, the Newbies Guide to Audio Recording Awesomeness.

Good luck.

Ken

How To Record Acoustic Music At Home – Step-by-Step

Recording acoustic guitar, along with some voices and other instruments, is one of the most common home recording activities out there. Today I thought I’d describe the techniques I use when recording this type of music. If you’d like to get an idea of how my recordings sound (pretty-much all acoustic/folk/singer-songwriter type music), you can hear a bunch of samples here: Ken Theriot’s Music.

Recording acoustic guitar, along with some voices and other instruments, is one of the most common home recording activities out there. Today I thought I’d describe the techniques I use when recording this type of music. If you’d like to get an idea of how my recordings sound (pretty-much all acoustic/folk/singer-songwriter type music), you can hear a bunch of samples here: Ken Theriot’s Music.

I recently finished recording a full CD of seasonal music, Ken and Lisa Theriot’s The Gifts of Midwinter, and I’ll be using one of the songs from that album as a sort of case-study for this article. Before we start, take a listen to the song here:

This song is close to “as basic as it gets.” It’s acoustic guitar, one voice singing, and a bass guitar. Here’s how I recorded it:

Recording Equipment

Let’s start with the microphones. For the guitar parts, I used a Shure SM-81, which is a thin pencil-style condenser microphone. The mic was plugged into my computer interface box, which in my case is an E-MU 1820m. It’s about 6 years old now. You can pick up a similar audio interface like that today starting at about $75. One example is the M-Audio M-Track, which you can get for just over $100. Plus it comes with Ableton Live Lite music creation software.

Anyway, that got the sound into my computer. To record the sound, I used my favorite recording and mixing software, Reaper, which you can pick up for $40 as long as it doesn’t make you more than $20,000 a year (honor system!).

For the voice I did the same thing as with the guitars, except there was a different microphone involved, the Rode NT2-A.

For the bass guitar, I used a “direct inject” box called the Line 6 Tone Direct similar to this one.

The Step-by-Step

First, I told Reaper to open a new project/song file and set the metronome to the correct tempo and time signature. I then turned on the click-track so everything I played would be synced to the same time.

Then as I listened to the click-track in my headphones, I played the guitar part onto the first track in Reaper. Next I started a 2nd track and played the same guitar part again. Then I panned the 1st track 100% to the right and the 2nd track 100% to the left. That gives the guitar a large stereo sound.

I opened a 3rd track and recorded one more guitar part. I put a capo on my guitar, transposed the chords, and played some different finger-style guitar in this higher register. I panned this guitar part about 20% to the right.

I then opened a 4th track and sang the vocal part, leaving it panned “dead-center” (panning – 0%).

Next I opened a 5th track and recorded a bass guitar part. I plugged the bass into the Line 6 box, told Reaper to bring sound in from the Line 6 device, and simply played along. I left the bass in the center of the stereo field (panned 0%) like the vocal.

I then listened to all the tracks together, altering the volume of each track so everything could be heard properly (this is the “mixing” part).

When it sounded good, I “rendered” or “mixed down” the project, resulting in a single stereo song file.

Finally, I opened the rendered song file in my audio editing program called “Adobe Audition.” I clipped off any extra space or noise from just before and just after the song, fading the end out smoothly. I made sure the overall volume as good, not too loud, not too soft, and saved it.

Finito. Have another listen to the finished product here: [jwplayer config=”Custom Audio Player-200″ mediaid=”15049″]

Please feel free to post any questions you may have about what I did to record this song in the comments section below.

Happy recording!

Ken