When connecting all the wires of a home recording studio, things can get very complicated very quickly. It is really important to try to keep things as simple as possible.

When connecting all the wires of a home recording studio, things can get very complicated very quickly. It is really important to try to keep things as simple as possible.

I just finished helping someone with their setup via e-mail. His stated problem that when adding a new track to previously recorded ones, the new track recorded not only the thing he was trying to add (say, a harmony vocal part), but also all the other stuff that had already been recorded! See our article article: Multitrack Recording Software: How Not to Record Already-Recorded Tracks for why this is not desirable.

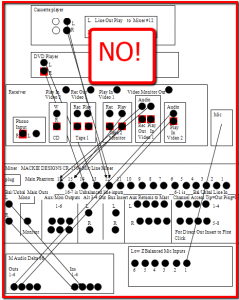

I asked him to send me a diagram of his setup because we were having difficulties trying to get the information straight just by talking about it in text e-mails. When I saw the diagram, I was pretty shocked at the complexity of all the inputs and outputs and how everything was being routed back and forth between 6 different devices. That was sure going to make it hard to understand the signal paths through the system.

The main problem was that he had sort of added a home recording studio to his existing entertainment center, which already had a DVD, cassette player, and “amplifier/receiver” with inputs and outputs. He added an external audio mixer (Mackie 1604) to all of this and used it as the hub to control volumes of everything in the system, even though the amplifier/receiver was already doing that job (uh-oh, two mixers!). He also (and THIS was the ultimate culprit for his woes) was using the built-in microphone preamp/input on the mixer to plug in his microphone (insert dramatic danger music here). This resulted in multiple feedback loops where one signal left a device and then came right back to or through that same device again. It was a nightmare.

Yes, there are microphone inputs on the mixer. He used one of them for a microphone. What’s so wrong with that? Well, in theory, nothing is wrong with that. If the mixer were ONLY being used for their microphone preamps to feed his computer sound card (an M-Audio Delta 66 with no mic preamp), that would have been fine. But that wasn’t the case, as he was using it for everything in his entertainment center as well.

I understand the motivation to sort of batch “all things audio” together. After all, it seems so efficient since you already have an area for all that stuff. But that can be the road to hell when anything goes wrong. The key is to keep it simple. Say it with me, KEEP IT SIMPLE. In this case I advised him to separate his home recording efforts from his entertainment center completely. He already had two mixers, in effect, the amplifier/receiver and the Mackie. He could leave the entertainment center stuff hooked to the receiver and take the Mackie away for the recording studio.

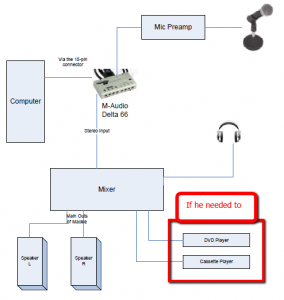

In drawing up what a separate recording studio setup would look like, the routing of inputs and outputs (or “gozintas and gozouttas” as Recording Magazine likes to put it) became much more clear and simple. It also became apparent that he needed a mic preamp for his mic(s) that was separate from his mixer. This solved the problem. See the diagram. If he absolutely needed the audio from the cassette player or DVD player for his home recording studio projects, it also shows how he could add that. In my case, I simply bought a separate cassette player for the studio for simplicity’s sake.

outputs (or “gozintas and gozouttas” as Recording Magazine likes to put it) became much more clear and simple. It also became apparent that he needed a mic preamp for his mic(s) that was separate from his mixer. This solved the problem. See the diagram. If he absolutely needed the audio from the cassette player or DVD player for his home recording studio projects, it also shows how he could add that. In my case, I simply bought a separate cassette player for the studio for simplicity’s sake.

The lesson here is keep it simple! The fewer cords and wires you have connecting things together, the simpler things will be. Resist the urge to route, re-route and double-back again just because you can (or think you can) get more “efficient” use from the gear you already have. Any cost savings you incur will be wiped out by the head-pounding and time lost that will inevitably result when something goes wrong. Trust me on this. I’ve been there, a lot!

Recording Tips and Techniques

Accent on Accents: The Curse of Dick Van Dyke

Hey Everyone, Ken here. This is the first in a new series of articles by Lisa Theriot on an interesting audio topic, accents. Voice actors are frequently called on to provide different types of accents when performing voice over jobs. One of the most requested types of accents is “British” (as if everyone in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all speak the same!–but that’s another harangue). This first entry in Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents series tackles the English Cockney accent. So without further ado, here is Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents #1:

Hey Everyone, Ken here. This is the first in a new series of articles by Lisa Theriot on an interesting audio topic, accents. Voice actors are frequently called on to provide different types of accents when performing voice over jobs. One of the most requested types of accents is “British” (as if everyone in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all speak the same!–but that’s another harangue). This first entry in Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents series tackles the English Cockney accent. So without further ado, here is Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents #1:

The Curse of Dick Van Dyke

When we lived in England, we found that it was commonly accepted among most Brits that the hands-down worst fake British accent ever was affected by Dick Van Dyke in the film Mary Poppins. Considering that the film is now decades old and still has the power to haunt, you have to think the trauma was pretty severe. So what were Dick’s big mistakes? Two very basic ones that a lot of people make when imitating accents: Overdo and Disconnect.

Overdo is pretty easy to understand. Most people recognize bad actors, because they look like they’re acting. (Good actors make you forget you’re watching an actor, because it seems so effortlessly genuine.) Bad accents are much the same. The actor will have a couple of signature sounds, like dropping initial ‘Hs’ and rhyming <day> with <eye> in the case of a Cockney accent, and they will flog them for all they are worth. Trouble is, people vary their vowel sounds based on how much stress the vowel receives. (And they vary their consonant sounds based on a number of factors, but that’s another article.) Try saying “mayday” and you’ll probably find your long-A sound is lighter on either syllable than it would be if you just said “day,” and oodles lighter than if you belted “day” like the last line of “Tomorrow” from Annie. A good fake accent varies vowel sounds just as you would in your natural speech. For contrast, listen to Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady. The Cockney accent was just as fake for the Belgian-born actress, who didn’t move to Britain until she was nineteen, but it seems much more natural. (People in the know would never believe she had been born within the sound of Bow bells, but real Cockney experts are the serious minority.)

Disconnect often accompanies Overdo. Actors have often drilled a few words or phrases, and when those are out, they think they’ve done their job and let the rest slide. Listen how often Dick will follow a hugely overdone long-A “eye” sound with a normal American long-A shortly thereafter. And all the little in-between words that make up most of our sentences aren’t worked on at all, so you get sentences like, “<accent> is in the <accent> with the <accent>.” Learning how things get strung together is the real key to selling an accent.

So what’s an aspiring Cockney to do? Hitting YouTube is a good start. And I’m not talking about links by Americans entitled, “How to Speak with a Cockney Accent,” I’m talking about actual Cockneys (there are plenty of them). Just listen. If you really want to learn, type yourself a script of what the person is saying and read along. Look at what they do with stressed and unstressed vowels. Pay attention to the little words. Pay special attention to what happens when two vowel sounds happen together (like “Diana_and” or “saw_a”). Read the script in your natural accent and then listen again. Try imitating syllables, then words, then phrases. It takes practice, but you’ll soon find you can do a good enough job to fool most Americans, and you definitely won’t sound like a Dick.

Lisa Theriot

Multitrack Recording Software: How Not to Record Already-Recorded Tracks

Multitrack recording software allows you to add tracks to previously-recorded tracks. This is mainly used in music recording where, say, you are a singer and want to record yourself singing harmony with yourself. You’d sing the melody first (usually) on one track. Then you’d open a second track and sing a harmony along with the melody on track 1, which requires you to be able to hear the playback from track one while you record track two. This also applies to adding other instruments to previously-recorded tracks, like adding a lead guitar part to a song, etc.

Multitrack recording software allows you to add tracks to previously-recorded tracks. This is mainly used in music recording where, say, you are a singer and want to record yourself singing harmony with yourself. You’d sing the melody first (usually) on one track. Then you’d open a second track and sing a harmony along with the melody on track 1, which requires you to be able to hear the playback from track one while you record track two. This also applies to adding other instruments to previously-recorded tracks, like adding a lead guitar part to a song, etc.

One thing you need to be sure of when doing multitrack recording is that your speakers need to be turned down or off when you record along with previously recorded tracks (unless you have someone else at the controls and the recording is happening in another room where the speakers can’t be heard). This may sound obvious but it is very easy to forget. If those speakers are audible when you’re recording a harmony or lead guitar track, the audio from those tracks will get recorded right along with the new track.

For example, if you recorded an acoustic guitar part on track 1, then wanted to add a vocal on track 2, your goal is to have each track contain ONLY those two things so that when you’re done, if you listen ONLY to track 2 (muting track 1) you would ONLY hear the vocal, not the guitar. This allows you to mix tracks, adjusting volumes relative to other tracks. However, if the speakers (playing the guitar part) were audible when you were singing that vocal part, track 2 would now have BOTH the vocal AND the guitar (picked up from the speaker) on it when played back by itself. That means that when both tracks are turned up, the guitar would be coming through twice, once from its original track (1), and once from track 2 where it was recorded along with your voice. You don’t want this!

So make absolutely certain your speakers are muted, turned off, unplugged or otherwise made inaudible when adding tracks to your song. Monitor previously recorded tracks with headphones when recording new tracks.

Church Sound: Passive & Active Direct Boxes, And How They Should Be Used

Home Recording: A DI unit, DI box, Direct Box or simply DI is an electronic device that connects a high impedance line level signal that has an unbalanced output (a.k.a., a piece of equipment) to a low impedance mic level balanced input, usually via XLR connector. The DI performs level matching, balancing, and either active buffering or passive impedance bridging to minimize noise, distortion, and ground loops. DI (pronounced dee EYE, not “DIE” as in “die feedback, die!”) is variously claimed to stand for direct input, direct injection or direct interface. The ends of each coil of wire protrude from the windings; one pair of ends is the input, and the other pair is the output. If the primary has more windings than the secondary, it is called a step-down transformer because the signal level and impedance are lower at the output than they are at the input. Passive DI Units A passive DI unit typically consists of an audio transformer used as a balun.

Read the full article here:

Church Sound: Passive & Active Direct Boxes, And How They Should Be Used

Mixing Beyond Stereo: Delving Deeper Into Aspects Of Sound & Perception

One of my favorite topics in the whole wide world:) – From the ProSound Web folks. Stereo mixing involves balancing out all audio signals equally for both sides, as human ear clearly understand from which direction sound is emanating to come up with a mix of multiple dimensions for more clarity without increased sound. Therefore, it is important to avoid sending identical signals to both speakers to minimize tonal, timing similarities, and avoid comb filtering. Therefore, one needs to send different signals to each side for better mix, good tonal balance, good sound reproduction etc, along with reduced audio signal in perceptual center for wider stereo quality sound.

Read the full article here:

Mixing Beyond Stereo: Delving Deeper Into Aspects Of Sound & Perception