I just read an article entitled “Can Award-Winning Recordings Be Made In A Home Studio?” But before I even read a word of the article, I had my hackles up (a thing my wife says when something gets her quickly in “defensive-mode”). That’s because the title alone made me say “what do you mean by “home studio,” and what awards are you talking about? We (my wife, Lisa Theriot and I) were finalists for an award called a “Voicey Award,” bestowed by Voices.com for voice-over recordings. So based on that, I’d say “of course” to the question posed in the title. We recorded our audio in a home studio, as did the eventual winner of our category.

I just read an article entitled “Can Award-Winning Recordings Be Made In A Home Studio?” But before I even read a word of the article, I had my hackles up (a thing my wife says when something gets her quickly in “defensive-mode”). That’s because the title alone made me say “what do you mean by “home studio,” and what awards are you talking about? We (my wife, Lisa Theriot and I) were finalists for an award called a “Voicey Award,” bestowed by Voices.com for voice-over recordings. So based on that, I’d say “of course” to the question posed in the title. We recorded our audio in a home studio, as did the eventual winner of our category.

The other thing that got me a bit rankled is that I generally despise the idea of awards for media productions. We make recordings for various reasons but few of us are out to “win an award.” Heck, most folks I talk to would be really happy if they could just get their audio to sound more professional. Who cares about an award? And my last word on awards and home studios is to point out how many major non-home studio recordings there are that have not won awards.

OK. Now that I’ve got that out of my system, let talk about the article.

First, the author, Bob Buontempo, specifies what he means by “award” (or at least level of award) when he says “i.e. – Grammy.” He’s talking specifically about music and not spoken-word/voice-over work. And he’s talking really prestigious, world-stage awards. That narrows things down a bit.

Next, he suggests that his definition of a home studio is “everything is in the spare bedroom,” because he states that it would be improbable to win a Grammy because you can’t fit a whole band (and that’s debatable) or an entire orchestra into a bedroom. Well, when you so narrowly define “home studio,” you make it much less likely for a recording made that way to be capable of winning a Grammy.

However, as the article goes on, there are suggestions that under the right circumstances, it is absolutely possible for a home studio recording to achieve Grammy caliber. It mostly comes down to the performance and the song. After that, it comes down to the knowledge of the engineer.

Yes, it is a fact that a large commercial recording studio is going to have more gear options, and that gear is likely to cost a LOT more than the typical home studio is likely to ever be able to afford. Also it is a fact that most recording and listening spaces in large commercial studios will have superior acoustics, which makes for more accurate mixing and better mastering.

Oh, yeah – the mastering thing. The author did not specify whether a home recording that is sent to a professional mastering facility counts as “a recording made in a home studio.” It should. Even the big studios send mixes to separate mastering facilities.

And this, for me, is the elephant in the room. Take 100 people off the street. Heck, even make them music loving people. Then ask them to listen and tell you the difference between a 24-bit/192KHz recording and a 16-bit/44.1KHz recording, and I would wager they could not tell you. I’d even be willing to bet most of them could not say which was an mp3 if you threw that into the mix! The purist may argue that the difference would be noticeable when played on a super high-end audio system. Maybe. But then what percentage of the music-consuming public are listening to high-definition music on high-end systems. A very tiny fraction.

So though on paper, the audio created in a home recording studio cannot, by the specs, go head-to-head with the major studio recordings, at the end of the day I say “so what?” People listening to music don’t look at specs. They listen to music. And the specs mean nothing if the recordings sound good. And recordings made in home studios are perfectly capable of sounding good.

Now for my final take on this question – do most recordings that people make in their home studios sound as good as the pros? In my experience they absolutely do not. That is because the gear is so affordable and anyone can get it now. That means there are thousands of people making home recordings with gear they don’t know how to use. I’ve said this many times – people with no audio knowledge, but with a million dollars worth of equipment can (and usually do) make crappy recordings if they know what they are doing. However, someone who DOES know what they are doing can make awesomely professional sounding recordings with a few hundred dollars worth of gear. It’s about the knowledge. One other thing I also say is that you can get that knowledge on Home Brew Audio. We make the daunting techno-jargon easy to understand so you can make great – even award-winning audio – in your home studio.

Cheers!

Ken

BTW, the original article is here: http://www.prosoundweb.com/article/can_grammy_winning_recordings_be_made_in_a_home_studio/

Audio Recording

How To Mic An Acoustic Grand Piano

Getting a great recording from a grand piano starts with mic placement. But with such a large instrument, there are just as many possible problems to run into as potential solutions. As with almost all audio endeavors, taking a little bit of extra time to get a good recording can save you lots more time and heartache later in the process.

You can read the full article about miking a grand piano here: http://www.prosoundweb.com/article/in_the_studio_close-miking_an_acoustic_piano/

Reaper Tips: Copy Selected Area Of Items

Of all the Reaper tips that I have to offer, some are so simple that at first they hardly seem worth mentioning. But they can save you a lot of time and a headache or two. That is the case with today’s tip – using the Copy Selected Area of Items action.

Of all the Reaper tips that I have to offer, some are so simple that at first they hardly seem worth mentioning. But they can save you a lot of time and a headache or two. That is the case with today’s tip – using the Copy Selected Area of Items action.

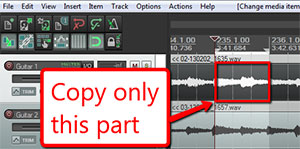

This tip is most valuable for those recording music (as opposed to voice-over stuff), though it is a good all-around thing to know about in either case. OK, so let’s say you just recorded an instrument track for your song – a guitar or piano maybe. And let’s say you recorded it to a set project tempo using a click track. To see why you might want to do this, see our article Using a Click Track For Recording Music.

Now let’s say that while listening to your newly recorded guitar track, you notice that on one measure, there was a little mistake, or a stray note. Maybe the strings buzzed. Whatever the issue, you really would rather not have that in the final recording. Do you need to record the entire track again? Surely not. Even in the old days of analog tape recording, you could fix that mistake by punching in/out to record just that section without the flaw. But we’re recording in the golden age of digital audio now! One of the best – if not THE best advantage of this is the ability to copy and paste. All you have to do is find another place in the song where you play the same chord or phrase. Then you can copy that and sort of “graft” it into the same spot where the offending audio lives.

This job will be much faster and easier if you have: recorded to a click track, and make sure to turn on the Snap tool in in your DAW. Doing the latter will make it quick and easy to select a correct measure or beat by snapping the edges of your audio selection (just click and drag to select). Then you can just paste the “good” sample that you just copied right underneath the “bad” section (on a new track – see our article Quickly Fix Audio Recording Mistakes by Overdubbing, Part 2 for the step-by-step, plus video, on doing this) all ready for pasting.

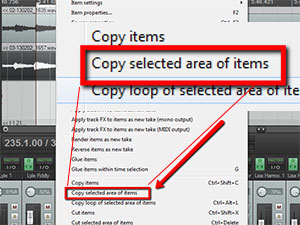

But wait. I kinda skipped right over how to copy JUST the correct measure or beat. If all you do is highlight a section of your audio and select Copy Items (or use CTRL-C), you will have copied the entire track’s worth of audio onto your clipboard! That will mess everything up when it comes time to paste. In Reaper, you have to choose Copy selected area of items instead. Just put your mouse onto the highlighted area of the audio, right mouse-click, and choose that from the drop-down menu (see the picture to the left). Then and only then will you have copied ONLY the section you want to paste over your mistake.

But wait. I kinda skipped right over how to copy JUST the correct measure or beat. If all you do is highlight a section of your audio and select Copy Items (or use CTRL-C), you will have copied the entire track’s worth of audio onto your clipboard! That will mess everything up when it comes time to paste. In Reaper, you have to choose Copy selected area of items instead. Just put your mouse onto the highlighted area of the audio, right mouse-click, and choose that from the drop-down menu (see the picture to the left). Then and only then will you have copied ONLY the section you want to paste over your mistake.

Believe me, the more you start taking advantage of the cut/copy/paste abilities in modern computer audio recording, this tip will come in very handy and save you time and frustration.

For more on how to use Reaper to record pro audio on your computer, come take the video tour of our latest tutorial course The Newbies Guide to Audio Recording Awesomeness 2: Pro Recording With Reaper.

Happy recording!

Woman Fined $220,000 For Uploading 24 Songs

Copyright is a touchy subject. It’s important for artists to be able to legally protect their work, but it also isn’t clear how much peer-to-peer file sharing actually damages artist revenue. There have been anecdotal reports that increased file sharing between fans has lead to increased concert attendance, and many artists skip the peer-to-peer networks and release entire albums in a “pay what you want” format. For example, In Rainbows by Radiohead was released in this manner in 2007.

Whether you think the United States copyright laws are fine as-is, or that they need to be strengthened or culled, this article discusses some of the more recent updates with the 2007 case against Jammie Thomas, who is charged with copyright infringement by uploading 24 songs to a peer-to-peer network. You can read the article here: http://www.digitalmusicnews.com/permalink/2013/20130211government

What Is an MP3?

![]() Unless you’ve been living under a rock on a very exclusive island for about a decade, you have at least heard and/or read the term “mp3.” But have you ever wondered what it is or what it really means? I was just going through the several hundred posts here on the Home Brew Audio website and discovered to my surprise that there were no articles or posts explaining what mp3s are. So I decided to write one.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock on a very exclusive island for about a decade, you have at least heard and/or read the term “mp3.” But have you ever wondered what it is or what it really means? I was just going through the several hundred posts here on the Home Brew Audio website and discovered to my surprise that there were no articles or posts explaining what mp3s are. So I decided to write one.

Let’s just start out by saying that music, an inherently non-computer thing, had to be made computer-friendly in this, the computer age. In the old days, music was played by musicians and we listened at concerts, in living rooms, etc. Then we found a way to record that music – to capture it so it could be listened to when the musician was not actually playing it. Recordings were made by converting the actual sounds in the air into something (an “analog” of the music) that could be played back on either a record player or tape machine. We didn’t concern ourselves too much with whether the analog was made of magnetic particles (tape) or etched into wax or plastic by electric signals (records).

Once it became feasible to use computers to digitize music into ones and zeros, digital music had to made usable to people who wanted to listen to music. At first we end-users didn’t know much had changed except that we could now get our music on things called CDs and play them back on CD players. It was an adjustment, but most everyone made the leap.

File Format – Size Really Does Matter

Eventually we discovered that we could “rip” our CDs into our computers. Once we realized that we could move out music around like this, and that the music was no longer physical in any meaningful way (like when we had to transfer CDs and records to cassette tapes in order the share them with friends), we also realized that sharing (not to mention storing, cataloging, etc.) music was going to get a lot easier. The problem was that the de facto default file type (the wav file) was massive and could not easily be shared or transferred across networks and the internet. In the 1990s, for example, it might take an hour or two to transfer one song in wav format. Though speeds and capacity are much better these days, wav files are still considered too large to use as web audio. It seemed that any effort to reduce the file size also reduced music quality so much that it wasn’t worth sharing any more.

Time To Use Our Brains – Literally

It turned out the reason the audio quality of the music suffered so terribly when folks tried to reduce the file size of wavs was that important audio information was being removed, information that human brains are very sensitive too. It was like a wav file were a stack of wooden blocks (each with a design on one side) on a scale. The weight of the stack is like the file size. If we imagine in this metaphor that we desire to see a stack of blocks around 10-blocks high. It’s beautiful to us. We want to share this stack with friends and family, but we cant because they weigh too much to lift. Someone gets the bright idea to remove several of the heaviest blocks to make the stack lighter. Great, except for one problem. The stack isn’t pretty any more. In fact it’s downright ugly (just like wav files that folks attempted to make smaller by removing data that made it sound good to us). Fail.

Next, a really smart friend comes to us with a new proposal. He shaves off the back sides of the heaviest blocks, in some cases removing quite a bit of the wood. In the end, quite a lot of wood has been shaved off the backs of these blocks and the weight of the stack is reduced so much that we can now pick the stack up easily and move it around. Everyone that sees it says it is still beautiful because they only see it from the front, where all the pretty pictures are. Yes, if they inspect the stack closely they will find that some work was done in the back, but they don’t really care about that because it’s the front they want to see.

As a rough idea of how much smaller an mp3 is than it’s wav counterpart – a 30 MB song’s wav file (about a 3 minute song) can be converted into an mp3 version that is only about 3 MB. The mp3 ends up being about a tenth the size!

Mp3s are kind of like that (what? – stay with me). Some smart people (specifically several teams of engineers working with the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) at Fraunhofer IIS, University of Hannover, AT&T-Bell Labs, Thomson-Brandt, CCETT, and others – reference: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MP3) figured out a way to remove bits (no pun intended) of information from audio files that human brains didn’t really notice were missing unless we listened really closely. Heck, even then most humans still can’t tell. The result was an mp3, which technically stands for “MPEG, audio layer III.” These files are small enough, but still sound good enough, that it became a fantastic way to share music with e-mail, on the web, or with any computer-like device. As a rough idea of how much smaller an mp3 is than it’s wav counterpart – a 30 MB song’s wav file (about a 3 minute song) can be converted into an mp3 version that is only about 3 MB. The mp3 ends up being about a tenth the size!

The Upshot

Files like mp3s are sometimes called “lossy” because some musical information is “lost” in order to make a small file by compressing the data (removing information to reduce the size). That is also why mp3 is sometimes referred to as a data “compression” format. This is not to be confused with “audio compression” as an effect, by the way. There are lots of other types of lossy file formats out there now as well, such as AAC and Ogg Vorbis to name a few. AAC is the type used by Apple’s iPod. Interestingly, iPods are still frequently referred to generically as “mp3 players.”

So now you know. You will never have to wonder again what an mp3 is or even what it stands for.

Use the knowledge wisely my friends.

Cheers!