If you’ve heard the term “audio normalization,” or just anything like “you should normalize your audio?” you may well wonder “what the heck does that mean? Isn’t my audio normal? Do I have abnormal audio?” And you would be right to wonder that. Because the term is not really very self-explanatory. So what else is new in the audio recording world?

If you’ve heard the term “audio normalization,” or just anything like “you should normalize your audio?” you may well wonder “what the heck does that mean? Isn’t my audio normal? Do I have abnormal audio?” And you would be right to wonder that. Because the term is not really very self-explanatory. So what else is new in the audio recording world?

To answer the questions in the title – let’s take them one at a time, but in reverse order, because it’s easier that way:).

Should I Care What Audio Normalization Is?

Yes.

That was easy. Next.

What Is Audio Normalization?

You COULD just use the definition from Wikipedia here. But good luck with that. As is typical with audio terminology, that definition is super confusing.

It’s actually pretty easy to understand and not really that easy to put into words. But I’ll try. When you “normalize” an audio waveform (the blobs and squiggles), you are simply turning up the volume. Honestly, that’s really it. The only question is “how much does it get turned up?”

The answer to THAT takes just a little tiny bit of explaining. First, let’s recall that with digital audio, there is a maximum volume level. If the audio is somehow pushed beyond that boundary, the audio gets really ugly because it distorts/clips.

Some Ways That Digital Audio Is Weird

This maximum volume level I mentioned is at 0 decibels (abbreviated as “dB”), by the way. Digital audio is upside down. Zero is the maximum. Average levels for music are usually between around -13 decibels to -20 decibels, or “dB” for short. Really quiet levels are down at like -70 dB. As the audio gets quieter, it sinks deeper into the negative numbers.

Yeah, digital audio is weird. But as long as you buy into the fact that 0 dB is the loudest the audio can gt before clipping (distorting), you’ll know all you need to know.

So Ways All Audio Is Weird

In case you didn’t know this, sound/audio is caused by waves in the air. Those waves cause air molecules to vibrate back and forth. The way a microphone is able to pick up audio is that those “air waves” ripple across the surface of a flat thing inside the mic. That causes the flat thing to move back and forth (in the case of a dynamic mic) or to cause back-and-forth electrical pressure in the case of a condenser mic. For more detail on this, check out my post What Is the Difference Between Condenser and Dynamic Microphones?

Some What Is The Weird Part?

Audio waves show up in audio software in a weird sort of way. For instance, you might expect the quietest audio to be at the bottom and the loudest to be at the top. But that isn’t the way it works with audio.

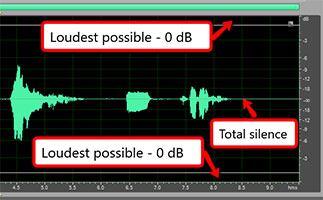

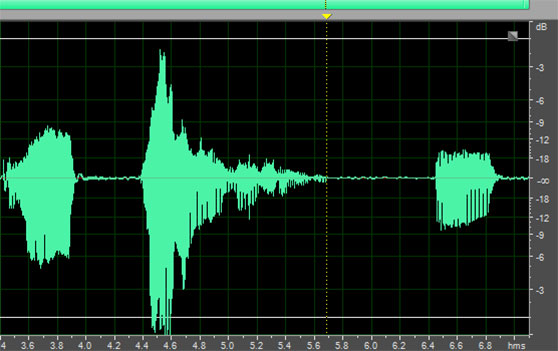

Because of the fact that audio comes from waves – the back-and-forth motion of air molecules – the loudest parts of audio are shown at the top AND bottom, and absolute silence is in the middle. Since pictures make things easier, see Figure 1.

So rather than thinking of the maximum allowable volume level as a “ceiling,” which is what I was going to do, let’s think of it like a swim lane. And in this swim lane, BOTH edges are boundaries not to be crossed.

This also means that when looking for the loudest part of your audio, you have to look both up AND down. Admit it. That’s a little weird. As it happens, the loudest part of the audio in our example below is in the bottom part of the audio.

Normalization Math

OK, back to normalization. Let’s get back the the question of how much audio is turned up when it’s being normalized. The normalization effect in audio software will find whatever the loudest point in your recorded audio is. Once it knows the loudest bit of audio, it will turn that up to JUST under 0 dB (you can set this in the Normalize controls to be AT 0 dB or whatever level if you want). So the loudest part of your audio gets turned up to as loud as it can be before clipping.

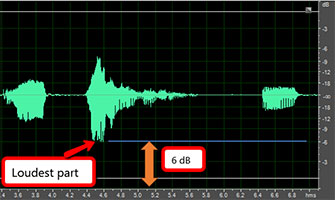

Let’s say the loudest part of your audio, which is a vocal recording in our example, is a part where you shout something. See Figure 2 for an example.

And let’s say that shout is measured at -6 dB. The normalization effect will do some math here.

It wants to turn up that shouted audio to 0 dB. So it needs to know the difference between how loud the shout is, and the loudest it could possibly be before distorting.

The simple math (well, that is if negative numbers didn’t freak you out too much) is that 0 minus -6 equals 6. So the difference is 6 dB.

Now that the software knows to turn up the loudest part of the audio by 6 dB, it then turns EVERYTHING up by that same amount.

Let’s look at a “before” picture of our example audio.

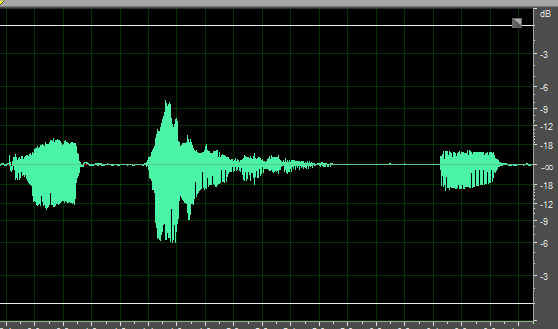

And here is what it looks like AFTER normalization.

That’s It?

Yeah. That’s it. Remember I said that audio normalization was really just turning it up? I know it took a fair amount of explaining, but yeah. The only reason to normalize your audio is to make sure that it is loud enough to be heard. That could be for whatever reason you want.

Use With Caution

As I have preached again and again, noise is the enemy of good audio. Before you even normalize your audio, you’ll want to be sure you’ve gotten rid of (or prevented) as much noise as possible from being in your audio recording. See my post series on how to do that here: Improve The Quality Of The Audio You Record At Home.

The reason it’s so important is that by normalizing your audio, you are turning it up, as we have seen. But any noise that is present in your recording will ALSO get turned up by the same amount. So be very careful of that when using this tool. Audio normalization is powerful, and so can also be dangerous.

Nice explanation!

Thanks!

Ken is not only a musician and music writer, he is an excellent teacher and speaker.

Thanks so much for the kind words, Shah!

Yes, a nice and simple explanation, with clear supporting images. Well done! This could be a nice preamble to then explain what dynamic processors like compressors can do beyond this point, helping to tame those loud parts of the audio so the rest can be turned up even more.

Thanks Karim! I thought I had something like this on compression as well. Let me check and I’ll put some links here. Here is one that’s fairly recent: https://www.homebrewaudio.com/using-audio-compressor-voice-over-jobs/ It talks about using compression for VoiceOver stuff, though the concepts are the same regardless of whether it’s for music or spoken word stuff. Here are a few other posts I did about compression: Improve Or Ruin Your Audio With an Effect Called Compression, and Vocal Compression Using Reaper’s ReaComp Effect Plugin.

Awesome, I am going to read those! I have invested a lot of time in learning dynamic processors and enjoy every article about it. I expect your posts will be as good as this one, so definitely adding them to my bookmarks! Thanks for the links!

Awesome! Let me know if you have any questions.

So where in the process do you normalize? Lets say you arr working with 4 waveforms in your DAW; a vocal, an acoustic, bass and drums. You have 4 tracks. Do you normalize each independently, Pre or post production, effects, etc? Or do you normalize the final mix?

the purpose of normalizing is really just to make sure the audio in file is at its own loudest possible volume (level). But since it is risky to just turn up audio without also turning up potential noise, I usually edit each file at least to make sure there isn’t a lot of noise in it first. So I edit first (de-noise, if it’s a vocal I remove mouth noises and possibly de-ess). Then I normalize it after. But if you’re working on a multitrack song in a DAW, and the level of the audio on a certain track is already sufficient, you may not need to normalize it at all. I don’t normalize EVERY track in a song if the levels are fine already. But when I’m working on a spoken-word/voiceover recording where the voice is the ONLY thing being produces, I always normalize it to make sure the person on the other end has the best chance of it being loud enough on their system without distorting/clipping. Hope that helps.