A very common question I see is “should I use compression in audio recording?” The best answer to this question is, as is so often the case, “Do you need compression in your recordings?”

Let’s start with a workable definition of compression in the audio recording sense. When you lower the volume of only SOME of your audio, usually the bits that are clearly louder than most of the rest of the audio you’re working with, you are “compressing” that audio. You would do this in order to allow you to raise the average loudness of the entire audio file.

How Can I Compress My Audio?

Now, this can be done manually, by which I mean you could open your audio in an editor, seek out all the areas where the wave forms (I like to use the term “blobs” instead) are loudest, then turn those bits down. But that can get REALLY tedious and time consuming. So to automate this process, a machine (nowadays done with software) called a “compressor” was invented. This allowed folks who really knew what they were doing to more quickly manipulate volume and loudness dynamics. The dark side of the situation, though, was that it allowed folks who were less expert to mess up their audio, and do it much faster and more efficiently than ever.

Compressor Settings?

There are all kinds of settings on a compressor that are better discussed in other articles. For a good idea of what those are, see my article and video – Vocal Compression Using Reaper’s ReaComp Effect Plugin.

For the moment I’d like to focus on a visual explanation of basic compression, since I strongly believe that those who use compressors to mess up their audio (usually without actually WANTING to mess up their audio) do it because they don’t have a really good grasp on what compression really is. This should help.

Lets Just Focus on What Compression Is

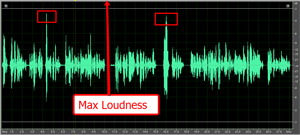

Take a look at figure 1, which is a voice narration file. I’ve boxed off the two loudest peaks.

If I tried to turn up the volume of this audio, all of the audio, including the 2 peaks, would “get bigger.” But there is a problem here. Do you see it? Look at the label in the picture pointing to Max Loudness. If any of the audio wave forms (blobs) get pushed beyond that border line the arrow is pointing to, you get nasty, awful digital distortion. Suffice it to say that the border line represents the upper boundary you must not cross.

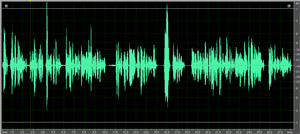

Knowing that, it should be easier to see why you can’t turn the loudness up very far before the peaks hit that boundary. And when that happens, none of the rest of the audio can get any louder either. See figure 3 to see what would happen if we told our editor to turn the file up until the loudest bit hit the upper boundary. There wasn’t a lot of change was there?

The blobs didn’t get much bigger (louder) did they? Oh no, whatever shall we do?

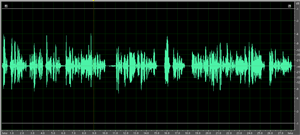

How about if we turn DOWN the level of JUST those two peaks? Let’s do that. Now take a look at figure 3 to see what our new file looks like. Notice that the

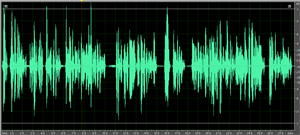

average level of the audio blobs is much more even now? THAT is what compression is for. Now that we don’t have just a couple of pesky peaks preventing us from turning our audio up without it distorting, we can raise the average level much higher, resulting in louder audio across the entire file. If we now tell our editor to raise the level of the loudest peak to maximum loudness (raising the rest of the audio by the same amount), we get figure 4. Compare

the picture in figure 4 with the one in figure 2. You will notice that blobs in figure 4 are much wider/bigger than the ones in figure 2 across the board.

Being able to increase the overall loudness level of your audio is just one benefit of compression, and perhaps its most common goal. when used wisely, this can also add punch and “up-frontness” to your audio. But don’t forget what compression actually accomplished for us BEFORE we were able to turn it up. It evened out the overall levels first, which gives a more consistent listening level to the user.

How Compression Would Help When Watching TV

I’ve often wished I had an audio compressor attached to my television for this very reason. Have you ever been watching a movie where the action scenes were so loud that you had to turn the volume down on the TV, only to find that now the talking parts are too quiet? Then you have to turn the TV back up to hear those parts. You end up turning the volume up and down throughout the show.

What about when the commercials on TV are much louder than the show itself? Don’t you wish you had a compressor to even out the volume so that it automatically turned the commercials down to the same level as your TV show?

I mentioned earlier that people frequently mess up their audio by over-use or incorrect use of compression. The most common problem is with music.

If you compress it too much, say, in order to make your mix louder than everyone else’s, you risk sucking out the dynamic range of the music. Changes in levels are important to the emotion of music. Over-compressing can flatten things so much that there is no more emotional flow to the music. That can also make it sound unnatural.

Also, compressors tend to impart certain sonic strangeness to audio when over-done, such as increasing sibilance (the sort of hissy sounds you hear when someone uses the letter “S”) in vocals, or audio “pumping” which is when the compressor is rapidly clamping down on loud audio and then letting up on quiet parts over and over.

So Should I or Shouldn’t I?

So back to the original question. “Should I use compression in audio recording?” Now that you understand what compression is, you can answer your own question. Do you want to even out the loudness of your audio? Then compression can help you. Do you want to raise the overall loudness of your audio without distorting? Compression can help you. Do you want to add some punch and ‘in-your-faceness” to a voice over? Compression can help. Just make sure you remember that it is really easy to overdo compression if you’re not careful.

Now go forth and squash your audio responsibly.

Ken

ps – Since this article was written, there have been several more posts that have to do with compression in some way. Since you’re now thinking about compression, you might be interested in learning more about it. See our other articles on compression here:

Using Multi-Band Compression

Home Recording: Singing As Loud As You Want

Compression For Punch and Presence

Hey Ken …

Thoroughly enjoyed your short straight to the point explanation of compression.

Thanks

Gary

Thanks Gary! Glad you liked it.

Ken

That was wonderful presentation. Clear and to the point.

thanks

Ganesh

Thanks Ganesh!

Ken

Great tips Ken! This article really explains compression and when to use it.

Thanks!

Friends at HomeMusicGear

excellent article…..here is a thought, why not decrease the use of a compressor. I started in the late 60s in studios and a favorite saying of engineers was “…We can fix It in the mix…” Why not try to accomplish audio without having to fix it later on. To me it is like saying turtle wax will make my faded paint job look new again. A lot of money is spent on after market plug-ins with compressors to “fix” music. Why not start by making the music good from the start. Keep up the good articles……

Norm/Redeyedcrow Music

I am very much in the “prevention” camp with you, Norm. These tools are there to help. But it is almost always best to try to prevent needing them if you can. I use compression sparingly, as it can easily ruin your audio if you’re not careful – as my other compression article – Improve Or Ruin Your Audio With an Effect Called Compression – suggests :).

BTW, I often do “manual” compression using automation envelopes, especially on vocals. This gives me total control over each increase or decrease in volume. It takes forever to do it this way, but usually ends up sounding much better than just feeding it through a compressor.

Thanks for the comment!

Wow! A very clear and concise explanation of what audio compression is! In mastering, unless the mix is heavily compressed, I find myself using multi-band compression 95% of the time. Even if it’s subtle, at the very least compression smooth the song and and kind of meshes it together.

Thanks John! that’s my goal – clear and concise explanations of things that are typically a bit hard for some folks to get their head around.