This is really pretty awesome. I’ve been looking for something like this because, well, to put it bluntly – my wife snores something terrible. that isn’t to say that I don’t. But mostly it doesn’t bother her now because I use a CPAP machine for sleep apnea and she sleeps with foam earplugs. But there are times when I just need to block out the low-frequency noise in a snore with some audio at night, in bed. But it’s really hard to sleep with headphones (or even regular ear buds) on. This might just be the solution. They are called bedphones.

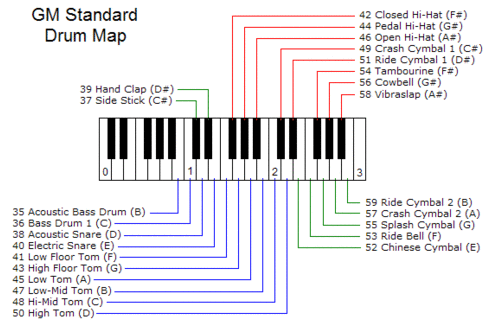

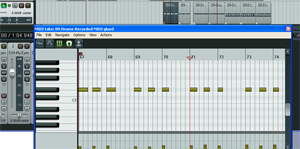

One of the coolest things about computer-based home recording studios is the wide-open world of virtual instruments. And of all the different kinds of instruments we can play via

One of the coolest things about computer-based home recording studios is the wide-open world of virtual instruments. And of all the different kinds of instruments we can play via