An interesting article about recording and using effects on drums. This article from ProSound Web is about different kind of drums used in studios and other music related programs.

Read the full article here:

In The Studio: EQ And Compression Techniques For Drums

Archives for July 2011

In Profile: Tom Danley, Exploring The Possibilities Of Audio Technology

This article is about audio technologies. Tom Danley shares his thoughts and experiences in what can be done with audio technology.

Read the full article here:

In Profile: Tom Danley, Exploring The Possibilities Of Audio Technology

Studio Compression: When, Why To Use Slow & Fast Attack Times

Home Recording Equipment: The Compressor.

Ratio and attack settings are the most important settings to learn about using a compressor. The attack setting tells the compressor how quickly it should compress the signals once it crosses the threshold. Whereas the ratio tells the compressor how much to compress once it crosses the threshold. The attack setting gives us idea about the time setting whereas the ratio gives us idea about the quantity to compress. You can brush up on compression and what these controls mean with our recent post – Vocal Compression Using Reaper’s ReaComp Effect Plugin

Read the full article here:

Studio Compression: When, Why To Use Slow & Fast Attack Times

Home Recording Studio Wiring – Keep It Simple

When connecting all the wires of a home recording studio, things can get very complicated very quickly. It is really important to try to keep things as simple as possible.

When connecting all the wires of a home recording studio, things can get very complicated very quickly. It is really important to try to keep things as simple as possible.

I just finished helping someone with their setup via e-mail. His stated problem that when adding a new track to previously recorded ones, the new track recorded not only the thing he was trying to add (say, a harmony vocal part), but also all the other stuff that had already been recorded! See our article article: Multitrack Recording Software: How Not to Record Already-Recorded Tracks for why this is not desirable.

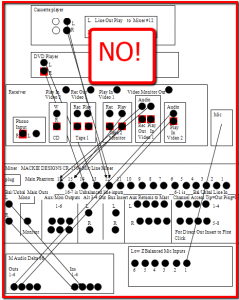

I asked him to send me a diagram of his setup because we were having difficulties trying to get the information straight just by talking about it in text e-mails. When I saw the diagram, I was pretty shocked at the complexity of all the inputs and outputs and how everything was being routed back and forth between 6 different devices. That was sure going to make it hard to understand the signal paths through the system.

The main problem was that he had sort of added a home recording studio to his existing entertainment center, which already had a DVD, cassette player, and “amplifier/receiver” with inputs and outputs. He added an external audio mixer (Mackie 1604) to all of this and used it as the hub to control volumes of everything in the system, even though the amplifier/receiver was already doing that job (uh-oh, two mixers!). He also (and THIS was the ultimate culprit for his woes) was using the built-in microphone preamp/input on the mixer to plug in his microphone (insert dramatic danger music here). This resulted in multiple feedback loops where one signal left a device and then came right back to or through that same device again. It was a nightmare.

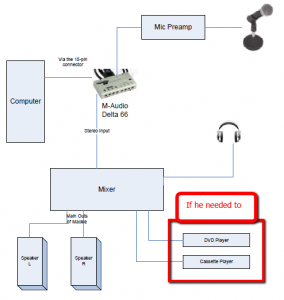

Yes, there are microphone inputs on the mixer. He used one of them for a microphone. What’s so wrong with that? Well, in theory, nothing is wrong with that. If the mixer were ONLY being used for their microphone preamps to feed his computer sound card (an M-Audio Delta 66 with no mic preamp), that would have been fine. But that wasn’t the case, as he was using it for everything in his entertainment center as well.

I understand the motivation to sort of batch “all things audio” together. After all, it seems so efficient since you already have an area for all that stuff. But that can be the road to hell when anything goes wrong. The key is to keep it simple. Say it with me, KEEP IT SIMPLE. In this case I advised him to separate his home recording efforts from his entertainment center completely. He already had two mixers, in effect, the amplifier/receiver and the Mackie. He could leave the entertainment center stuff hooked to the receiver and take the Mackie away for the recording studio.

In drawing up what a separate recording studio setup would look like, the routing of inputs and outputs (or “gozintas and gozouttas” as Recording Magazine likes to put it) became much more clear and simple. It also became apparent that he needed a mic preamp for his mic(s) that was separate from his mixer. This solved the problem. See the diagram. If he absolutely needed the audio from the cassette player or DVD player for his home recording studio projects, it also shows how he could add that. In my case, I simply bought a separate cassette player for the studio for simplicity’s sake.

outputs (or “gozintas and gozouttas” as Recording Magazine likes to put it) became much more clear and simple. It also became apparent that he needed a mic preamp for his mic(s) that was separate from his mixer. This solved the problem. See the diagram. If he absolutely needed the audio from the cassette player or DVD player for his home recording studio projects, it also shows how he could add that. In my case, I simply bought a separate cassette player for the studio for simplicity’s sake.

The lesson here is keep it simple! The fewer cords and wires you have connecting things together, the simpler things will be. Resist the urge to route, re-route and double-back again just because you can (or think you can) get more “efficient” use from the gear you already have. Any cost savings you incur will be wiped out by the head-pounding and time lost that will inevitably result when something goes wrong. Trust me on this. I’ve been there, a lot!

Accent on Accents: The Curse of Dick Van Dyke

Hey Everyone, Ken here. This is the first in a new series of articles by Lisa Theriot on an interesting audio topic, accents. Voice actors are frequently called on to provide different types of accents when performing voice over jobs. One of the most requested types of accents is “British” (as if everyone in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all speak the same!–but that’s another harangue). This first entry in Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents series tackles the English Cockney accent. So without further ado, here is Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents #1:

Hey Everyone, Ken here. This is the first in a new series of articles by Lisa Theriot on an interesting audio topic, accents. Voice actors are frequently called on to provide different types of accents when performing voice over jobs. One of the most requested types of accents is “British” (as if everyone in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all speak the same!–but that’s another harangue). This first entry in Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents series tackles the English Cockney accent. So without further ado, here is Lisa Theriot’s Accent on Accents #1:

The Curse of Dick Van Dyke

When we lived in England, we found that it was commonly accepted among most Brits that the hands-down worst fake British accent ever was affected by Dick Van Dyke in the film Mary Poppins. Considering that the film is now decades old and still has the power to haunt, you have to think the trauma was pretty severe. So what were Dick’s big mistakes? Two very basic ones that a lot of people make when imitating accents: Overdo and Disconnect.

Overdo is pretty easy to understand. Most people recognize bad actors, because they look like they’re acting. (Good actors make you forget you’re watching an actor, because it seems so effortlessly genuine.) Bad accents are much the same. The actor will have a couple of signature sounds, like dropping initial ‘Hs’ and rhyming <day> with <eye> in the case of a Cockney accent, and they will flog them for all they are worth. Trouble is, people vary their vowel sounds based on how much stress the vowel receives. (And they vary their consonant sounds based on a number of factors, but that’s another article.) Try saying “mayday” and you’ll probably find your long-A sound is lighter on either syllable than it would be if you just said “day,” and oodles lighter than if you belted “day” like the last line of “Tomorrow” from Annie. A good fake accent varies vowel sounds just as you would in your natural speech. For contrast, listen to Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady. The Cockney accent was just as fake for the Belgian-born actress, who didn’t move to Britain until she was nineteen, but it seems much more natural. (People in the know would never believe she had been born within the sound of Bow bells, but real Cockney experts are the serious minority.)

Disconnect often accompanies Overdo. Actors have often drilled a few words or phrases, and when those are out, they think they’ve done their job and let the rest slide. Listen how often Dick will follow a hugely overdone long-A “eye” sound with a normal American long-A shortly thereafter. And all the little in-between words that make up most of our sentences aren’t worked on at all, so you get sentences like, “<accent> is in the <accent> with the <accent>.” Learning how things get strung together is the real key to selling an accent.

So what’s an aspiring Cockney to do? Hitting YouTube is a good start. And I’m not talking about links by Americans entitled, “How to Speak with a Cockney Accent,” I’m talking about actual Cockneys (there are plenty of them). Just listen. If you really want to learn, type yourself a script of what the person is saying and read along. Look at what they do with stressed and unstressed vowels. Pay attention to the little words. Pay special attention to what happens when two vowel sounds happen together (like “Diana_and” or “saw_a”). Read the script in your natural accent and then listen again. Try imitating syllables, then words, then phrases. It takes practice, but you’ll soon find you can do a good enough job to fool most Americans, and you definitely won’t sound like a Dick.

Lisa Theriot